The Days of the Scorchers

In the early 1890s a number of design improvements created the style of bikes we are familiar with today. While the older high-wheelers had been fun for the brave and athletic, the new "safety bicycle" appealed to a broader audience of casual riders. The bicycle brought a transportation revolution and new independence for women and young people.

Chicago Tribune illustration from June 9, 1895

By the summer of 1894 Chicago had fully caught "wheel fever." Newspapers reported on the start of Annie Londonderry's journey from Boston to Chicago attempting to be the first woman to bike around the world. And local bike clubs discovered that Palmer Square made the perfect oval track for racing.

Chicago's boulevards were originally designed for leisurely carriage rides. With no freight wagons and no streetcar tracks, these roads also made excellent bicycle byways. Within the parks some roads were asphalted, but most of the boulevards between were crushed gravel which was far better for riding than the rugged stone and slick wooden block pavements of city streets downtown.

Membership in bicycle social clubs boomed and new organizations proliferated in the mid 1890s. Some clubs had womens' auxiliary groups as well. Many groups had their own club houses for meeting before and after rides. For a time the West Side Cycling Club had its clubhouse on the northeast corner of Humboldt Boulevard & Cortland Ave. The cycling clubs organized noncompetitive social rides and festive night-time lantern parades along the boulevards. A grand bike procession passing through Palmer Square in May 1896 featured almost 6000 riders from all the bike clubs in the city riding in the colorful uniforms of each group.

Since the late 1880s cyclists had established a 5-mile route for competitive bike races starting at North Avenue, then up Humboldt Boulevard, six loops around Palmer Square, and back again. Another popular 10-mile loop started in Garfield Park then followed the boulevards through Humboldt Park up to Palmer Square and then returned south. There were popular routes on other south-side and west-side boulevards, but the Palmer Square loop became known as the best place for "scorchers" to set new bike speed records.

The Chicago Tribune began paying attention to the Palmer Square races in 1894. On Sunday, July 29 of that year, a thousand spectators came to Palmer Square at 6:30 am to watch a 10-mile race with 46 competitors organized by the Chicago letter carriers bike club. A.E. Smith won in 29 minutes, 15 seconds. He later went on to break the speed record from Chicago to New York.

The popularity of the 5-mile Palmer Square loop increased during the summers of 1895 & 1896. More and more cycle clubs applied for permits from the West Side Park Commission to hold races on the boulevard. The Tribune reported on races held almost every Saturday afternoon and Sunday morning from June to September, often several each day. Many of these races attracted thousands of spectators. It's not recorded if women cyclists, with their controversial bloomer outfits, ever raced in Palmer Square, though one race in 1895 was cancelled when officials declared the men's uniforms to be too revealing!

For the residents of Lyndale Street, especially the children, it must have been a thrill to see the weekly excitement of the races just a block away. Jacob Bonggren's 17-year-old son Alf, at 3101 Lyndale, caught the wheeling bug and joined the Lake View and Garland Cycling Clubs in 1897. He was a strong enough rider to earn the "scratch" position at the start of several road races that year.

Even outside the official road races, its likely that cyclists often trained on their own at Palmer Square or set up informal races. On Thanksgiving 1895, John "The Terrible Swede" Lawson planned to ride around the square for 24 hours to set a new record, though there's no record on whether he succeeded.

1897 portrait of Desire Bruno, 34-year-old Canadian who held the 100-mile record in Palmer Square of 5 hours 28 minutes

In 1896 several bike clubs organized a 25-mile Memorial Day race from suburban Wheeling (an appropriately-named place to start), down Milwaukee Ave and through Palmer Square following the boulevards to Garfield Park. 600 cyclists signed up for the race, and thousands of spectators and amateur cyclists came out to watch.

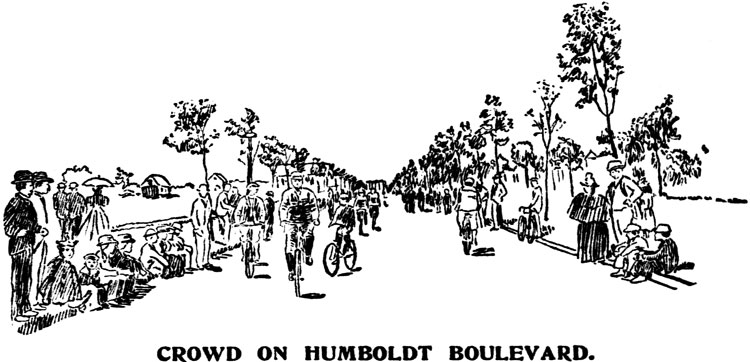

The Tribune illustration below shows the festive scene of neighbors gathered to watch the race. The view is looking north on what is now Kedzie Boulevard, either just north of Fullerton or just north of Palmer Square, which means the spectators pictured may be Lyndale Street neighbors. Beyond the spindly young trees lining the boulevard we can see a few widely-spaced cottages and two-flats on the side streets in the open prairie.

Chicago Tribune illustration from May 31, 1896

A cycle-riding Tribune reporter in 1895 described a short cut east of here, from Palmer Square down Palmer Street, then up California to Fullerton heading to the lake: "There are not many houses in this part of town just yet, but those that are there look as if their owners were prosperous and thrifty."

Perhaps the bike races became too popular in the end. Even though the cyclists had the support of local alderman George S. Foster (head of the Clover Cycling Club), in 1897 the West Side Park Commission stopped giving approval for organized races in Palmer Square despite repeated appeals by cycling clubs. Future races would be held more often at specially-built wooden tracks like the velodrome in Garfield Park as the sport became more professionalized.

Until 1900 there were only a few houses around Palmer Square, so there were few neighbors impacted by the race crowds. The lots around the square were developed over the following decade, including bicycle manufacturer Ignaz Schwinn's mansion at the southeast corner of the square, which was built in 1906 long after the big races were over.

The Memorial Day bike race from Wheeling continued for several years, but either the Tribune lost interest in reporting on it or it ended after 1898. Soon the new fad of automobiles would steal the public's attention and cycling's popularity faded. On the very same day that the Terrible Swede planned his endless circuit of Palmer Square, the nation's first auto race was held in Chicago, from Hyde Park up the lakefront to Evanston and back along the boulevard routes used by cyclists.

Six cars started the race on a dreary day of sleet and drizzle, but only two passed Palmer Square in the afternoon and made it to the finish. If Lawson was out there in the cold pursuing his record, he could have easily lapped the horseless carriages puttering along at 6 or 7 mph, like a hare passing a tortoise.