The Lost Mansion

One of the larger houses in the area once stood at the southeast corner of Palmers Square. Known locally as the "Schwinn Mansion", the greystone house sat on the east side of a large property extending from Humboldt Boulevard all the way to Whipple Street. The house was built in 1906 for Ignaz & Helen Schwinn, of Arnold, Schwinn & Co., the largest bicycle manufacturer in the U.S.

Ignaz Schwinn, Mortorcycle Illustrated, June 14, 1917

Ignaz Schwinn was born in 1860 in a small town in central Germany. His father died when he was 11, and Ignaz went to work to support his mother and younger siblings. In Frankfurt he found work in the machine shops making high-wheel bicycles, which were all the rage in the 1880s. Schwinn rose through the ranks and in his after hours drew his own designs for bicycles with two equal-sized wheels. Known as the "Safety" in England where they were first produced, this is the style we recognize as the modern bike. His ideas were not initially accepted by the local manufacturers, but at age 29 he was hired by Heinrich Kleyer to design a factory and production line which produced some of the first Safety bicycles in Germany.

Ignaz was a headstrong young man, and soon found himself in disagreement with Kleyer over the best design of a coaster brake. Within a year he left Germany for Chicago with his wife Helen and a dream of running his own factory the way he wished. At the time Chicago was home to dozens of bicycle manufacturers and was the center of the America's fast-growing bicycle industry. The design innovations of the new safety bicycle, such as pneumatic tires, chain drive, improved brakes and new assembly-line manufacturing methods lowered the bicycle's price and broadened its appeal to a wider audience of casual cyclists. The bicycle brought a transportation revolution and new independence for women and young people. It was a revolutionary fad and sales were booming.

After several years of working for other firms, Ignaz Schwinn partnered with meatpacker and investor Adolph Arnold in 1895 to start his own bicycle factory. Four years later the company purchased the March-Davis cycle factory at 1856 N. Kostner and moved its operation from downtown to Hermosa. Ignaz and Helen Schwinn and their young children were living in a greystone three-flat at 3115 W. Fullerton the following year.

In the late 1880s, cycling clubs established a course for competitive bike races around Palmer Square, which at that time had few houses built around it. From North Ave up the boulevard and around the square six times totalled 5 miles. In mid-1890s organized races were held nearly every summer weekend, and thousands of spectators came out to watch the "scorchers" set new speed records.

By the time the Schwinns hired architect Frederick Gatterdam to build the mansion on Palmer Square in 1905, the amateur races had moved to professional velodromes such as the one in Garfield Park, but perhaps Schwinn was familiar with the site from watching those races a decade earlier.

Interest in cycling crashed nearly as quickly as it had grown, and tastemakers moved on to the new hobby of automobiling. While many bicycle manufacturers went bankrupt, Schwinn survived with diminished sales. In 1911 Schwinn purchased the Excelsior motorcycle company from Frederick Robie (of the well-known house in Hyde Park) and the company committed to this new market a few years later by building the world's largest motorcycle factory on Lawndale Ave next to the Bloomingdale freight line. The factory produced motorcycles until a collapse in demand in the early 1930s, which refocussed the company on bicycles and led to the balloon-tired chrome cruisers for which they are still famous today.

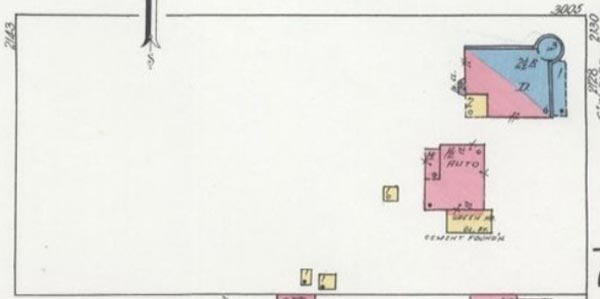

The mansion in the northeast corner of a block-wide lot. Detail of 1921 Sanborn insurance map, Library of Congress.

The fifteen-room Schwinn mansion on Palmer Square was a rectangular building with a pyramidal tile roof and a prominent round 3-story tower with a conical roof. The house was faced with Bedford limestone, rugged at the base and smooth above. Horizontal stringcourses break up the bulk of the tower. Two asymmetrical bay windows provided views of Palmer Square from each floor of the north wall of the house. A colonnaded porch and scrollwork stair to the front door faced east onto Humboldt Boulevard.

Ignaz Schwinn driving the wrong way on Palmer Blvd in front of mansion. Courtesy Logan Square Preservation.

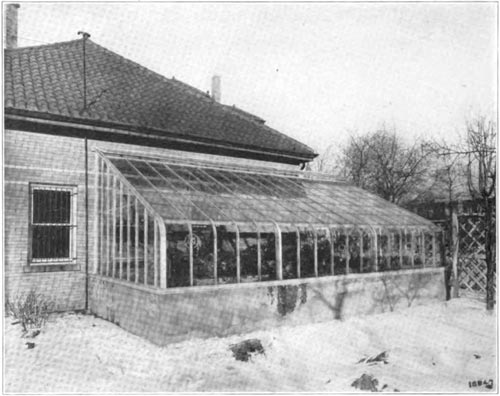

Behind the mansion, to the southwest, stood a 1½ story brick automobile garage with a footprint nearly half the size of the mansion. A 25-foot greenhouse was attached to the garage. Legend has it that Ignaz installed a turntable so that the motorcars would not need to back out toward Humboldt Boulevard. Every morning Ignaz woke early and made the two-mile drive to his factory, the first to arrive.

Schwinn greenhouse and garage building. American Greenhouse Manufacturing Co., 1922. Shakespeare Apartments in distance at right.

The architect Frederick E. Gatterdam was also a German-American immigrant, four years younger than Ignaz Schwinn. He had arrived in Chicago as a teenager and found work as a draftsman before hanging out his own shingle as an architect at age 27. He formed a short-lived partnership with architect William Krieg in the 1890s, then worked on his own again. In 1909 Gatterdam built a six-flat at 2555-2557 W. Logan Boulevard where he lived with his wife Margaret and their four children. In the 1910s he worked on a number of houses and storefront buildings in Logan Square with builder Olaf Egeland who was his neighbor on Logan Boulevard. Later in his career he became known as an architect of breweries.

Two years after completing the Schwinn mansion, Ignaz Schwinn again hired Gatterdam in 1907 to design a large apartment building for an empty lot across the street on the east side of Palmer Square. The stone-fronted Shakespeare Apartments stretch over 150 feet along Humboldt Boulevard and Shakespeare Avenue and included 30 large 6-8 room units. Some Schwinn employees may have lived in the building, but in the 1910 and 1920s censuses, the majority of tenants were office clerks and small business owners working in other industries.

The 1929 stock market crash wiped out much of Ignaz Schwinn's wealth and investments. The Excelsior motorcycle company ceased production in 1931 and the 71-year old Ignaz gradually relinquished control of the company to his son. Frank Schwinn refocussed the company on bicycles and in 1933 released the first sturdily-built balloon-tire chrome cruisers which would become bestsellers for decades and revitalize the lagging bike industry.

In the 1940s, local bike dealer Oscar Wastyn Jr. recalled seeing the retired Ignaz napping on the front porch of his mansion on Humboldt Boulevard. He passed away at home in 1948 at age 88.

In 1955 Frank Schwinn and his wife Gertrude, who was active at nearby St. Sylvester Catholic Church, donated the house and property to the church. In March of that year the city zoning board of appeals approved plans for a new school building on the site up to 16 feet from the property line, rather than the 30 feet required in a residential zone. The dining hall at the new school was named in honor of the Schwinn family and their now-lost mansion.

This article appeared in slightly different form in the Logan Square Preservation 2020 house walk tour guide "Pillars and Porticoes".