Detail of Carl Winter's tavern from ca. 1908 postcard image courtesy Logan Square Preservation.

No Free Lunch

The circa 1908 postcard image of Lyndale & Sacramento streets above provides a glimpse of the lost house on the corner at 2954 W. Lyndale, a long-gone saloon with the original address of 125 Johnston Ave. From the angle of the shadows we can guess that the photo was taken in the mid-morning. Two barkeeps in traditional starched shirts and ties watch the photographer from the stoop before preparing for the lunch crowd. To their left, a door leads to the upstairs apartment where the proprietor lived with his family.

Though the awning is furled it is possible to make out the word "BUFFET" on the side and the 125 address on either side of the saloonkeep's name "CARL WINTER".

A larger wood sign above with gilded letters also shows the name of the saloon between logos for the Pabst brewing company, which also appears on a sign hanging off the side visible to north- and south-bound travelers on Sacramento Avenue.

The first proprietor of the corner saloon was Bernhard "Barney" Steil, who was born in Luxembourg in 1849 and came to America in 1872. Steil was 37 years old when he bought the building on Lyndale Street in 1889, newly married with an infant daughter and new to the saloon business.

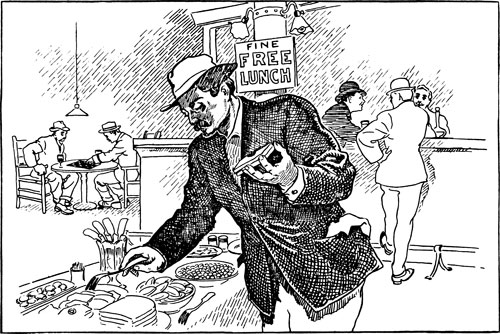

The saloon at 2954 most likely featured a long wooden bar along the right-hand wall and a brass rail for drinkers to rest their feet while standing. A few tables sat in back with the day's newspapers. The cartoon below shows a typical interior which may have been similar to Steil's saloon. The noontime free lunch buffet was a tradition which began in Chicago in the early 1870s but spread nationwide over the next decade. Barney Steil's wife Elise likely prepared the daily spread of coldcuts, pickles, hard-boiled eggs, rye bread, sardines and other finger foods, while Barney minded the bar and made sure all the freeloaders bought a 5¢ beer in order to enjoy the free lunch.

"The Saloon – Poor Man's Club" from March 1, 1909 issue of industry magazine Mida's Criterion, reprinted in The Saloon by Perry Duis.

Writer George Ade reminds us not to get too nostalgic about these buffets in his 1931 remembrance The Old Time Saloon: "As a matter of cold truth, the average free lunch was no feast for Lucullus or 'Diamond Jim' Brady, but a stingy set-out of a few edibles which were known to give customers an immediate desire for something to drink." A few salty snacks probably sufficed as a "lunch" in many of the cheaper saloons, but we have no record of how Elise and Barney's spread rated.

Elise Steil many years later in a 1921 passport photo. Source: Ancestry.com

In the 1870s and 80s, the number of saloons in the city skyrocketed as the increasing popularity of lager beer, new pasteurization technology and Chicago's exploding population created what seemed like an unlimited market for a working class entrepreneurs such as Steil to enter with relatively low startup costs.

During Chicago's "beer war" of the 1890s, an influx of foreign capital and local mergers led breweries into a competitive spiral that drove the price of beer down from $8 per barrel to as low as $4 per barrel, which encouraged the opening of more taverns. Kitty-corner from Steil's place, there were short-lived saloons at 3003 and 3005 W. Lyndale listed in city directories from the 1890s.

In July 1899, Steil hired architect William Klewer to add a second-story addition to the back of the saloon with an upstairs banquet hall. Many saloons featured such meeting rooms which could be reserved for group meetings, weddings and parties. The corner saloon was a public meeting place and center of community life on the street. Perhaps Steil's place was similar to family-friendly bars run by German saloonkeepers, and on weekend afternoons a few women may have joined their husbands for a glass. A 1901 law passed by prohibitionists required all saloons to lock their front doors on Sundays, but that simply meant that customers would use the side door, which would have been on Sacramento to the left of the image above.

Due to low profit margins and fierce competition the saloonkeeper worked long hours to stay in business, opening at 5am for customers in need of a morning bracer on the way to work and staying open to midnight or later. Closing-hour laws were rarely enforced by authorities. To make enough money to pay back debts to the breweries who financed the business, saloonkeepers had incentive to never turn away a customer, no matter their age or state of inebriation.

Many wives and relatives of customers resented the saloonkeeper for taking their husbands away from family and cashing their paychecks for drinks even before the workingmen made it home on payday. No doubt a number of neighbors on Lyndale Street disliked the corner saloon and crossed the street to avoid passing in front of its swinging doors with their beery smells and sounds.

To reign in the surplus of saloons, temperance activists passed a state-wide law in 1883 to raise the saloon licensing fee from $150 to $500, but the law instead increased the number of saloons as breweries stepped in to pay for the license in exchange for exclusive rights to sell their brand at the bar. Some breweries built their own "tied houses" from scratch while others paid for the mortgages on existing saloons.

A 1906 directory lists Carl Winter as the saloonkeeper at 2954. Barney Steil was apparently no longer able to continue working due to ill health and depression and the family moved to an apartment near the California L station. In the spring of 1907 he committed suicide at home. His widow Elise sold the property in October 1908, not to bartender Carl Winter, but to Gustave & Hilda Pabst, owners of Pabst Brewery. A new law that went into effect in May of that year had raised the liquor license fee from $500 to $,1000. Perhaps Winter could not afford to buy the property and liquor license, and instead became a Pabst employee and tenant rather than a bar owner.

After the sale, Carl Winter stayed on as saloonkeeper living in the upstairs apartment with his family. His wife Lena likely prepared the noon buffet. Their son Charles was in his early 20s, a vocal student at a music conservatory. Perhaps he entertained the barflies with a song now and then. He and his father could be the bartenders in the postcard photo above.

But Winter was never the full owner of the saloon, and tied-house saloonkeepers were often let go by their brewery bosses, with up to 60% turnover in 1901. In 1913 an ad appeared in the Tribune to sell the business to a new saloonkeeper investor:

Whether the ad was placed by Winter or by Pabst is not clear but in the next year Winter and his family moved to a new saloon at 3400 W. Fullerton. After going bankrupt there, he ran a billiard hall at 2958 W. Fullerton for several years before retiring.

1919 advertisement for non-alcoholic Pablo. Source: Pabst website

When Prohibition went into effect in January 1920, the corner saloon became a "soda parlor," but how much did it change in character? Pabst's new Pablo "near beer" malt beverage was probably served there, with stronger drinks surely available to those in the know. A 1922 police banquet in the upstairs meeting hall even featured "good beer," instead of near-beer imitations. While police looked the other way, the saloon probably remained much the same as before Prohibition, at least for a few years. Gustave Pabst sold the property in May 1925 to neighbor Edwin Tolf.