The United States Capitol is the finest example of Federalist architecture in the country. The building's Neoclassical design takes inspiration from the great buildings of ancient Rome, but also follows the architectural styles of England and France. The structure has a complex history, with major changes and additions as the United States and its government have grown. Many architects, engineers and artisans have contributed to the Capitol we know today.

When Pierre L'Enfant surveyed the streets for the new nation's capital in 1791, he selected a slope known as Jenkin's Hill to be the site of the new "Congress House." Upon reviewing the plans for the new Federal City, Thomas Jefferson substituted the word "Capitol," inspired by the Capitoline Hill in Rome. From its height, the statehouse would overlook a wide boulevard to the west and a diagonal avenue northwest to the site of the new President's House.

In 1792 Jefferson announced a design competition for the Capitol with a $500 prize. None of the initial submissions showed the proper grandeur or architectural skill necessary for the center of government, but a late entry by amateur architect Dr. William Thornton showed enough promise for President Washington to select Thornton as first Architect of the Capitol.

Jefferson formed a committee including the runner-up entrant Stephen Hallet, who had professional architectural training, and James Hoban, the winner of the President's House design, to assist in drawing up plans which merged the interior of Hallet's design with Thornton's exterior.

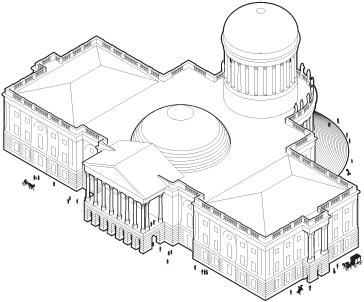

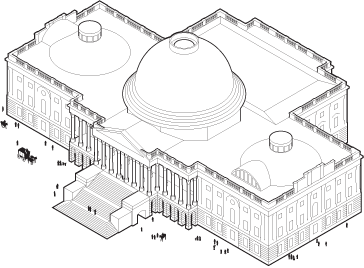

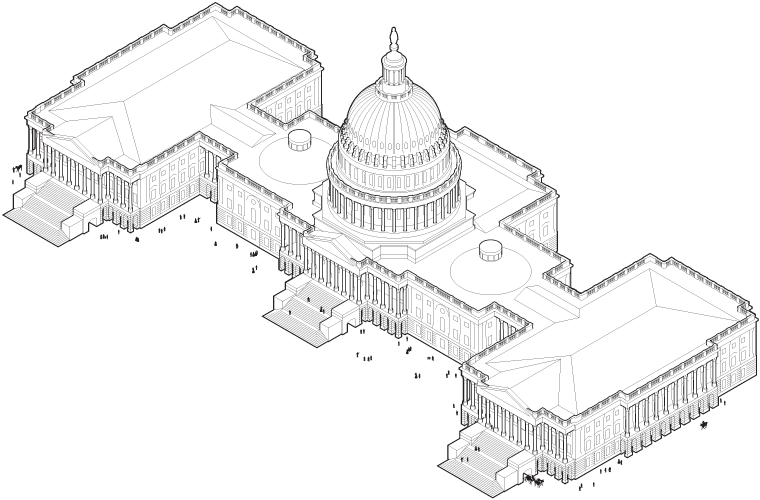

The planned Capitol was to be built from brick faced with whitewashed sandstone. The legislative chambers were on the first floor and public galleries reached by a broad staircase on the west. The Senate would occupy the north wing and the House of Representatives the south, with a middle section featuring a domed rotunda and a temple-like colonnade as a monument to Washington (later suggested as a shrine where the founding father would be entombed).

The building needed to be finished by the fall of 1800 in time for the government's planned move from Philadelphia, so workmen began digging foundations before the design of the central section was finalized.

President Washington laid the cornerstone for the new statehouse with pomp and circumstance in a grand Masonic procession and ceremony on September 18, 1793. But the subsequent work progressed in fits and starts as funding was available, with work done by hired workmen and slave laborers.

In 1800 the north wing of the building was complete, with the Senate in its chamber and the House, Supreme Court and Library of Congress crowded into various committee rooms until a temporary brick structure was built for the representatives.

When Benjamin Latrobe was hired as Architect of the Capitol in 1803 he discovered the interior walls of the north wing already deteriorating due to shoddy construction. Over the next eight years Latrobe redesigned the interior layout, moved the legislative chambers to the second floor and switched the approach to the east with an imposing staircase leading up to a widened portico.

Although the central section was still incomplete, the north and south wings of the Capitol were an impressive sight when the British Army invaded Washington in 1814. In retaliation for the Americans' sacking of York, the capital of Upper Canada (now known as Toronto), the invaders broke into the building, stacked the wooden chairs in the legislative chambers and set them alight.

Fortunately the exterior walls and some rooms survived the fire. A five-year restoration rebuilt the rest of the interior according to Latrobe's redesign. Charles Bulfinch became Architect in 1818, and work at last commenced on the central dome. The original design took inspiration from the low dome of the Pantheon of Roman antiquity, but Congress requested a higher top to the building. Bulfinch's compromise had a masonry interior built to classical proportions with a bulbous secondary copper-sheathed crown on top.

President Andrew Jackson disbanded the office of Architect of the Capitol in 1829, but as the U.S. continued to add states and congressmen, the need for an expansion of the building grew.

In 1851 the Senate announced a new contest to enlarge the Capitol. Many architects submitted proposals adding a larger structure to the east, or wings to the north and south, even a scheme to make a mirror-image building across a vast courtyard. Thomas U. Walter was finally selected, with the directive to design wings connected to the main building by narrow corridors. President Millard Fillmore laid the new cornerstone on July 4, 1851 with another parade and Masonic honors.

Jefferson Davis had taken an interest in the expansion since his days as a Senator. As newly appointed Secretary of War, Davis transferred the project to the War Department and appointed Captain Montgomery C. Meigs to assist Walter as engineer. Meigs hired Italian painter Constantino Brumidi to decorate the interior with rich carvings and classical murals.

The increased length of the building made Bulfinch's round dome awkwardly out of proportion, so Walter drew up plans for a taller spire. Though inspired by neoclassical church architecture, the structure was made from modern lightweight cast iron, the largest ever built. Sculptor Thomas Crawford created the nearly twenty-foot tall statue of Freedom at the crown of the dome. In Crawford's first versions the statue wore a liberty cap, the Roman symbol of a freed slave, but due to the protests of Davis (a slave owner and future president of the Confederacy), the statue was given a feathered eagle helmet.

The extension project was not yet finished when the Civil War began, and construction languished for some time, but President Abraham Lincoln viewed its completion as an important symbol for the cause of the Union government. By the end of 1863 the dome exterior was in place, but it would be another four years until all the details of the project were finished.

With the addition of new western states, Congress again needed more room. Frederick Law Olmsted designed a basement-level office expansion under the terrace on the west side of the building in 1886. Later, space was added in separate office buildings across the street connected to the Capitol by underground subway trains.

The last major change to the exterior of the Capitol was the 1958 eastern front extension, which created a replica of the central facade, portico, columns and pediment carved from Georgia marble, placed 32 feet out from the original walls. The old 1828 portico columns were later relocated to a monument at the National Arboretum.

More recently, a large underground visitor center opened just east of the Capitol in 2008, with space for exhibitions, tours, and shops.

Despite the long history of clashing egos and visions of its architects and artisans, to say nothing of those of the politicians inside, the United States Capitol stands harmonious as one of the most beautiful and elegant seats of government in the world.

Order the Capitol Building model book

Order the Capitol Building model book

Dover Publications, 2017: ISBN 978-0-486-81474-2. Paper model ©Matt Bergstrom, Wurlington Press