Reed & Associates

by Matt Bergstrom & Tom Greensfelder

In the 1940s, the predecessor of one of Chicago's most famous toy design companies produced a wide range of die-cut paper models. Spurred by the lack of durable materials available for commercial production during WWII, Reed & Associates created paper toys for young children both as entertainment and wartime propaganda. Since the 1920s, Chicago was one of the most prominent centers in the United States of the new industries of advertising and cartoon comics. Reed & Associates took advantage of both with their pioneering promotional tie-ins.

The Beginnings

Bayard "Judd" Reed (1905-1961) was born in Ottawa, Illinois, the oldest of three sons of a businessman who owned a newspaper and later a box manufacturing company. As a young man, Reed moved to Chicago to become a commercial artist. He married Dorothy Stevens in 1928 and the couple had one daughter. Reed worked in the art department of the Montgomery Ward department store headquarters illustrating catalogs for a number of years before starting Reed & Associates with Eoina Nudelman.

Judd Reed portrait from 3 Flying Models of Famous Allied Fighting Planes, Reed & Associates, 1944.

Eoina Nudelman (1892-1967) was born in Odessa, Ukraine. He came to Chicago at the young age of fifteen. By his mid twenties he was working at Newman Monroe Co., a printing and engraving shop best known today for the colorful travel posters they produced. After serving in the U.S. Army as a machine gunner in World War I in France, he came home to Chicago with a plan to return to Europe to study art.1

Eoina Nudelman passport photo 1924

While in Paris in 1921, Nudelman married Hélène Cadet who had a young daughter from a previous relationship. The couple returned to Chicago where they had another daughter of their own. The family went back to France in 1924 where Eoina joined an ad agency working with the Printemps department store. Foreshadowing his future work, the Printemps—like the other major department stores in Paris at that time—produced a line of advertising paper models. Although we don't know if Eoina was involved in their production, he was no doubt aware of them.

He returned to Chicago after his wife Hélène passed away in 1941. He was working for a Chicago department store designing animated window displays when he and Reed met.

Reed and Nudelman were friends before founding Reed & Associates as a company in 1941 or 1942. They set up offices in Nudelman's home in the Tree Studios Building, a historic artists colony of apartments with attached studios in Chicago's River North neighborhood.

Their partnership was formed at a critical time in the U.S. toy industry. After the United States entered World War II, the War Production Board enacted restrictions on materials strategic to the war effort in 1942 and 1943. Companies that had previously made toys from tin or steel now switched to wood and cardboard, while their factories were re-tooled to make metal parts for war equipment.

For some time, Reed's wife Dorothy had suffered from severe depression. She was eventually confined to Manteno State Hospital.2 While visiting his wife at the state hospital, Reed met Marvin Glass (1914-1974), who would become the third associate in Reed & Associates.

Glass was born Marvin Goldberg in Chicago, the only son of a clothing salesman. His parents were Jewish immigrants who had come from Poland and Ukraine a decade earlier, and like Eoina he grew up speaking Yiddish at home. Glass had a difficult childhood. His mother was eventually committed to the same hospital as Reed's wife. Marvin Glass was much younger than his new artist friends and possessed a far more forceful personality. His energy and passion as a salesman would be transformative for Reed & Associates.3

The materials restrictions of the war impacted consumer goods slowly. Steel trainsets and tin wind-up cars were still advertised in department store catalogs for the 1942 Christmas season, but a year later metal toys were largely replaced by trains and cars made of wood or thick cardboard. In the toy industry journal Playthings, the celebrated paper model designer Wallis Rigby wrote several editorials addressed to toy designers who may be new to using paper and cardboard. He urged them to design toys with the unique qualities of these materials in mind rather than just substituting for the conventional materials they had used previously.4

Would Reed and Nudelman have chosen paper as a material for their toys without the wartime restrictions? It's impossible to say, but with the two artists' training in illustration, and Nudelman's interest in animated displays, they were well suited for designing paper models and moving paper toys.

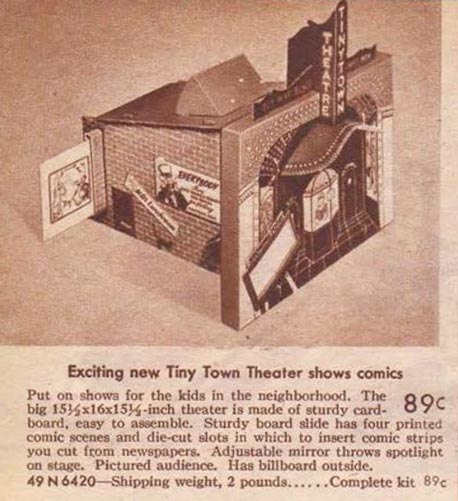

In the beginning, Reed & Associates may not have had enough money to manufacture or distribute anything they designed. An early paper toy created by Nudelman was the "Tiny Town Theater", a miniature cardboard model of a movie theater. Children could peek inside the theater to see cartoons on the screen slid into a slot at the back of the theater which was illuminated by a mirror in an opening in the roof. The company sold the design to a publisher for $500. Decades later, Glass recalled the decision with regret, claiming that the $1 toy had been a hit and the publisher had made $30,000 from it. From then on he vowed to retain royalty rights for all of Reed & Associates' future products.5

Sears-Roebuck catalog listing of Tiny Town Theater, 1943.

Reed & Associates formed partnerships with other companies to finance production of their designs. The Electric Corporation of America (ECA) had been founded in early 1942 by Leo Maranz to build freezers, lamps and electric fans. But after the implementation of war rationing, the company had to find something else to manufacture. They switched to toys, art sets and figurines made from non-restricted cardboard, paper, plaster and wood.6

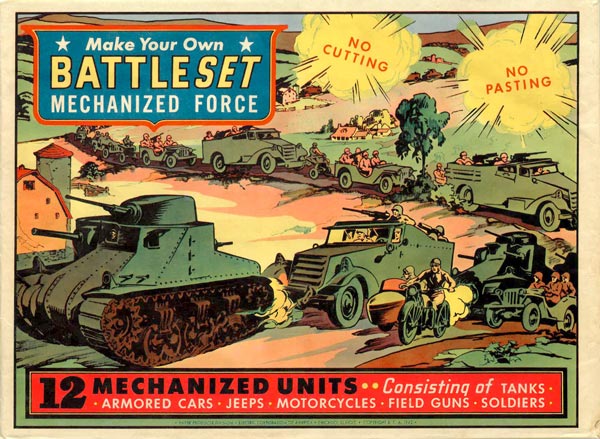

Reed and Nudelman provided the designs for the new toys as well as illustrations for the packaging and advertising, while ECA handled the manufacturing and marketing. In late 1942 the partners published their first paper toys: a set of die-cut sliding puzzles, a playset of tanks with stand-up soldiers and a complex model of a boxy aircraft carrier with a string-pull mechanism to launch miniature flying airplanes.

Battle Sets published by E.C.A. Paper Products Division, 1943.

These first toys must have been successful sellers because the following year ECA published at least a dozen more die-cut playsets, models and games as well as assembled toys made from heavier cardboard. In recognition of their contribution, Reed & Associates could now, for the first time, proudly label their creations "A Reed Toy" right on the box.

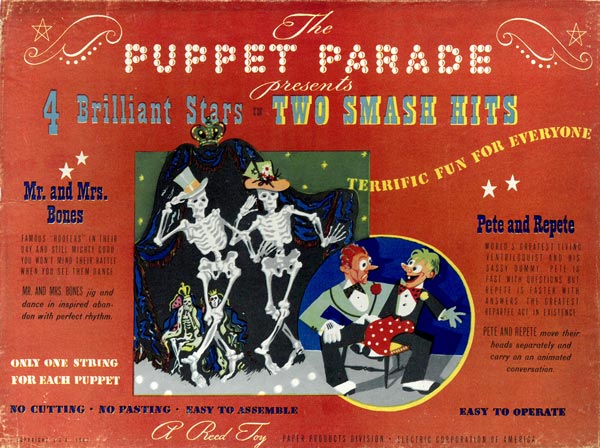

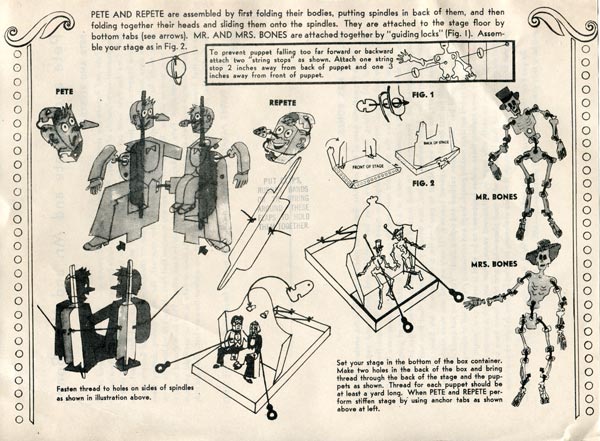

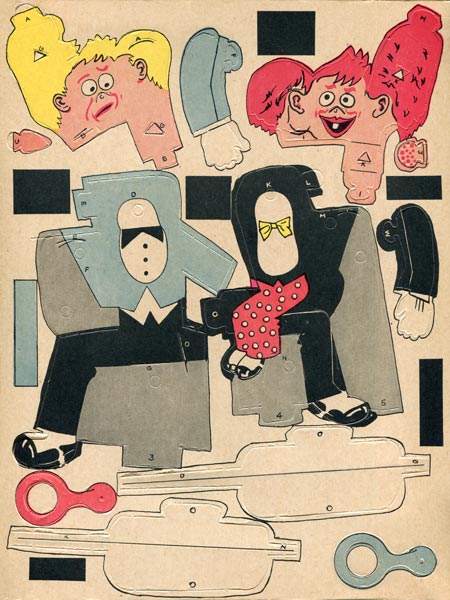

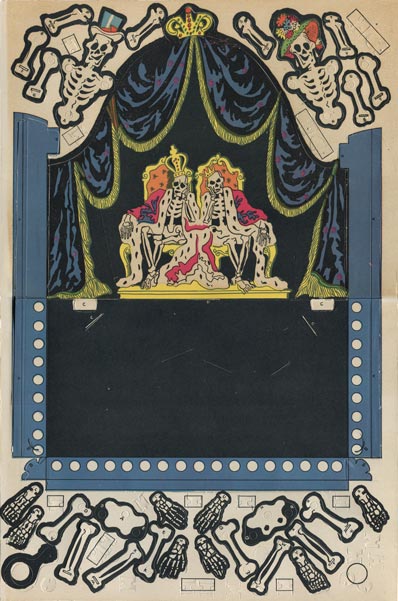

Though Eoina Nudelman didn't get his name printed on the packaging, his artistic style is clearly behind the series of five "Puppet Parade" toy kits made in early 1943. The die-cut cardboard toys included a stand-up stage that fit into the top lid of the box. Children could pull strings to move the cardboard puppets on the stage or make them dance by wiggling the strings. Five toy sets covered five different types of theatrical performance from drama to comedy to music. The storybook-like biographies of the puppet performers printed on the back of the instruction sheet appear to be products of Nudelman's imagination rather than characters who might have already been familiar to children.

Mr. Bones and Pete & Repete Puppet Parade, box and sheets, E.C.A. Paper Products Division, 1943.

Other ECA toys designed by Reed & Associates published that year included a Ferris wheel and a carousel that used small pieces of glass to make a tinkling sound as they turned. The Skyhawk Squadron Action Airfield featured a cardboard catapult pulled by a string to launch simple airplane models, probably similar to the aircraft carrier model published previously. These complex kits sold for a relatively-expensive $2 each.

ECA Toys ad, November 1944

Judd Reed's extensive research on aircraft lead to several games and toys. Wefto and Spot-Em were family board games published by ECA which challenged players to identify aircraft silhouettes. Reed also designed a cardboard volvelle (a turning disk within a holder) airplane identifier that could fit in a soldier's pocket.7

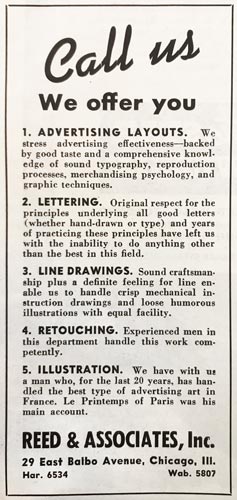

By the end of 1943, Reed & Associates moved their operations out of Nudelman's studio to an actual office in an Art Deco building at 29 E. Balbo just south of Chicago's downtown Loop. They hired a secretary and a crew of tradesmen to create the complex die-cut templates used for the models. The company also advertised their services as a general-purpose art and design studio for clients needing illustration and photo retouching. Reed & Associates also designed stacking wooden block toys and baby toys which were licensed to other toy companies to manufacture.8

Reed & Associates, Inc. ad, Printers Ink, Feb 25, 1944.

Soon after opening the new office, the company launched a new design project with their new business partner, Martin P. King. King was a fountain pen salesman who had designed a hit board game called Battleship Checkers in early 1942. He and his wife Ruth formed a partnership with ad agency executives Edward Larson and Nelson McMahon—appropriately named King, Larson, & McMahon—to market the game.9

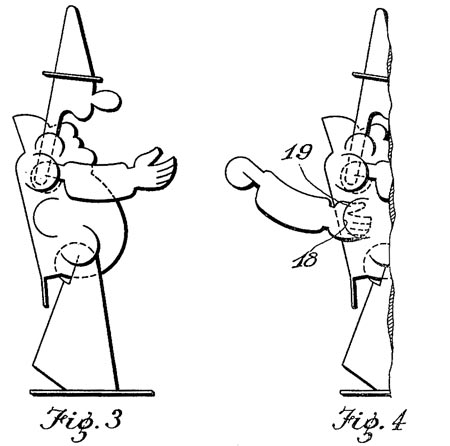

In early 1944 Reed & Associates partnered with King, Larson & McMahon to design a paper doll with movable limbs they called Hingees. King may have come up with the concept and the name, while Nudelman figured out the paper engineering and patented the design. The spiral-shaped connectors of the Hingee figures could move easily to change the position of the arms and legs, yet were stiff enough to hold the figure upright.

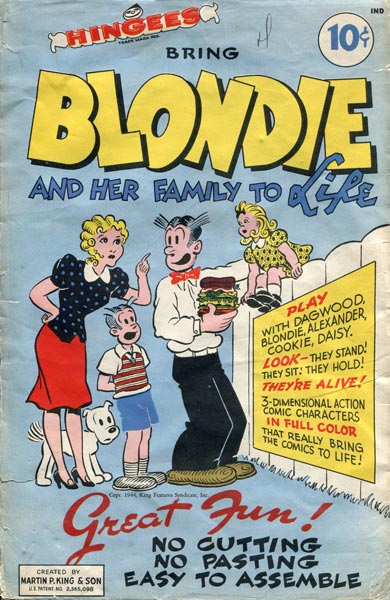

Bring Blondie and Her Family to Life Hingees, Martin P. King & Son, 1945.

Detail of Hingees Patent #2,365, 098 by Eoina Nudelman for Martin P. King, Feb 12, 1944.

Marvin Glass, who was a bit of an exaggerator, bragged that Martin King had invested $200,000 (over $3 million nowadays) to bring the Hingees to life.10 The toy took several months for Reed and Nudelman to develop and was finally printed and packaged for advance sales in October 1944. King, Larson & McMahon secured a licensing agreement with King Features Syndicate (no relation to Martin P. King) for the use of the popular comic strip characters of Blondie, Popeye, The Katzenjammer Kids and Bringing up Father. Chicago-based Famous Artists Syndicate licensed the cartoons Smokey Stover, Dick Tracy, Little Orphan Annie, and Terry and the Pirates, as well as the famous real-life lion-tamer Clyde Beatty, who was well known from his travelling circus and starring role in the 1936 film The Lost Jungle. Ten different Hingees were produced in 1944, as well as a deluxe boxed set which included them all. Each was printed in four colors on a die-cut sheet of cardstock that was folded to fit into an envelope. The toys sold for an affordable 10¢.

In 1945 Larson and McMahon left the partnership and King renamed the company Martin P. King & Son (though his son Benjamin was then only one year old). The toys were reprinted that year with the new company name in a more colorful envelope, though the model sheets inside remained unchanged.

In the early days of Reed and Nudelman's company, Marvin Glass had been hired as a salesman. But as the company grew he took on a larger role as promoter, spokesman and idea man. In 1944 he bought out his two partners and took over as president of the company. In later interviews Glass claimed that Reed and Nudelman were not interested in working with customers, while he was more dedicated to the success of the company.11

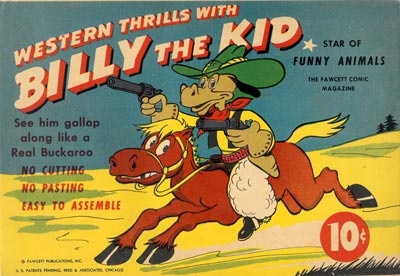

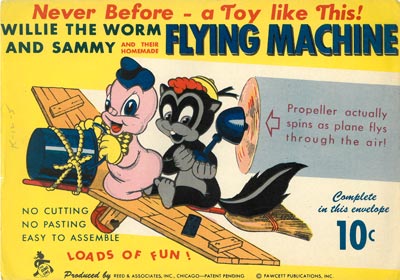

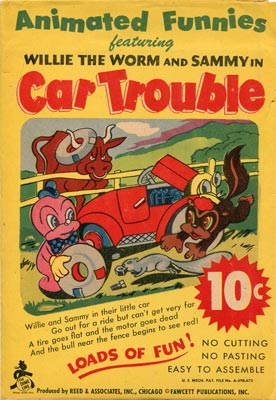

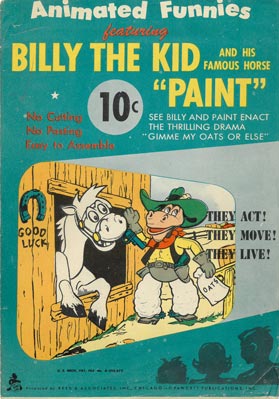

In 1944 Reed & Associates began a new partnership with Fawcett Publications, a publisher of childrens comic books. Again Reed & Associates designed the models, the packaging and die-cuts, while Fawcett handled the printing, production and distribution of the finished products. At the time, Fawcett's Captain Marvel was the most popular comic book character in the United States, selling 1.3 million comic books a month. Reed and Nudelman patented a design for a glider with a fold-up tail, which they customized into several different comic-book super hero paper toys.

Captain Marvel model envelopes, Fawcett Publications, 1944.

Like the Hingees, the models were printed in four colors on a folded sheet of die-cut cardstock and sold in a paper envelope with instructions on the back. The colorful covers of the packaging looked like comic books, and they were most likely stocked next to the Fawcett comics on the same shelves. The new "Dime Line" toys sold for the same price as a comic book at 10¢.

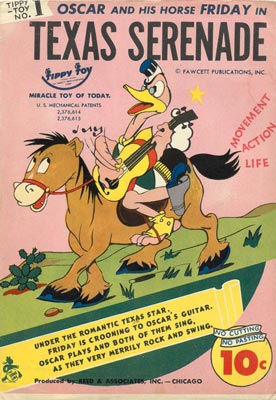

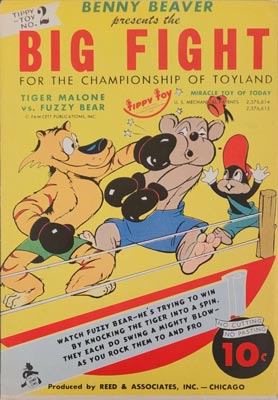

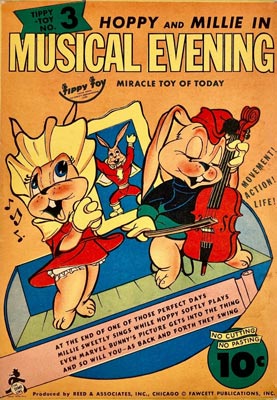

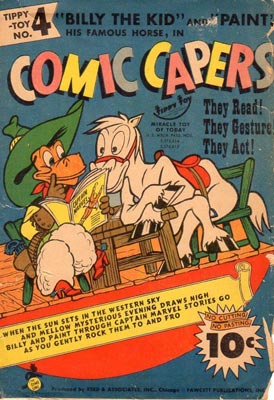

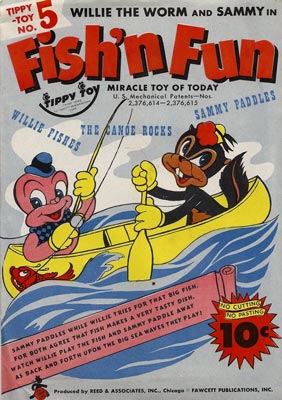

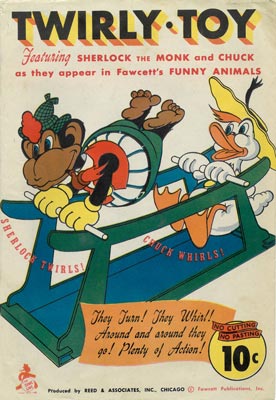

In March 1945 Nudelman patented a toy design which is animated by rocking on a round base. The mechanism became the basis of a new "Tippy Toy" line of cardboard toys featuring characters drawn by artist and animator Chad Grothkopf from Fawcett's "Funny Animals" comic books. The superhero Hoppy the Marvel Bunny was a spinoff from the already popular Captain Marvel stories. Reed & Associates went on to design cardboard games, puzzles, and animated picture cutouts using the Funny Animals in different combinations. The die-cut toys were simple to punch out, but the more complex moving toys may have been a challenge for younger children to assemble.

"Funny Animals" paper toys by Reed & Associates, Fawcett Publications 1945.

Reed Models

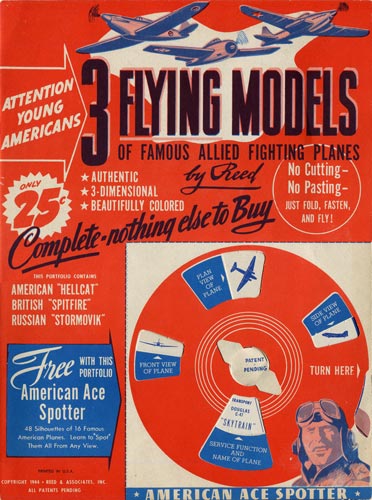

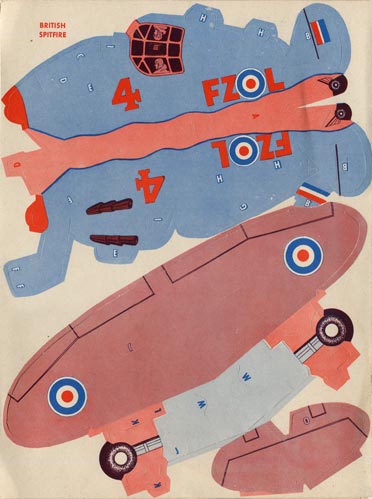

Reed & Associates published several paper models without the investment and distribution of other partners. In 1944 Judd Reed designed "3 Flying Models of Famous Allied Fighting Planes". The 25¢ model kit printed on a long folded piece of cardstock included a built-in "American Ace Spotter" similar to Reed's earlier volvelle cardboard airplane identifier. The kit's American Hellcat, British Spitfire and Soviet Stormovik fighter models are roughly 1:55 scale in size. They are somewhat realistic in profile, though not very accurate to the shape of the real planes. The models are fairly simple and made from only a few die-cut shapes. The designs featured some unusual innovations: the nose of the plane is held together by wrapping a piece of paper over the fuselage and tucking it into a slot which may have been designed to add a little extra weight to the front for flying the model. The wings meanwhile are stiffened by a lengthwise fold that forms a right-angled airfoil. Judd Reed's proud signature is on the front of the package, and his photo accompanies a short message for young builders.

3 Flying Models of Famous Allied Fighting Planes, cover and sheet, Reed & Associates, 1944.

3 Flying Models of Famous Allied Fighting Planes, completed models, Reed & Associates, 1944.

Of course, Reed's flying planes had competition. Wallis Rigby published Models of Fighting Planes of the United Nations in 1942, which featured both realistic stationary and simple flying models of some of the same fighter planes. Then, in March 1944, Connecticut commercial artist Fred Myers patented a simple warplane promotional design for General Mills' Wheaties cereal featuring Jack Armstrong, the famous radio program pilot. Myers' elegant fighter plane models used a penny as weight for better flying. Though Reed's designs were clumsy by comparison, perhaps children liked that they were die-cut and did not need to be cut out with a knife or scissors.

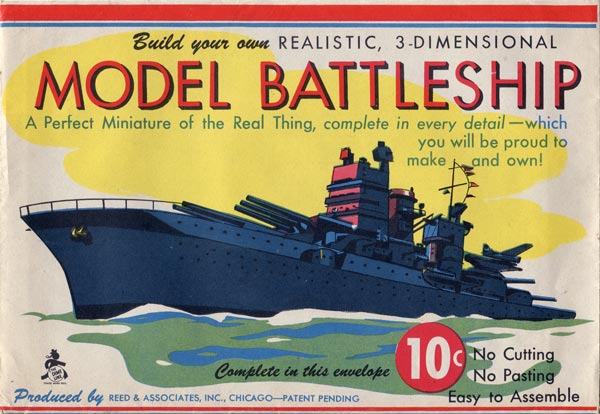

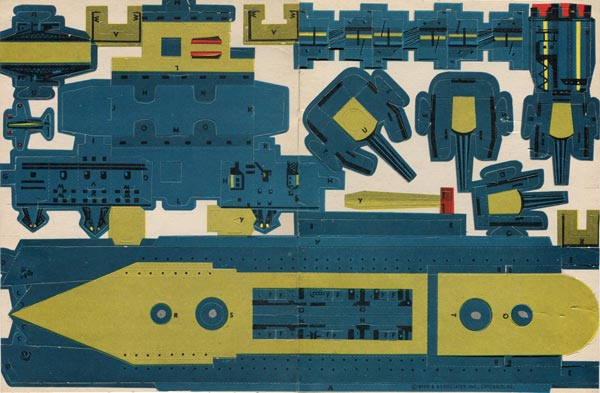

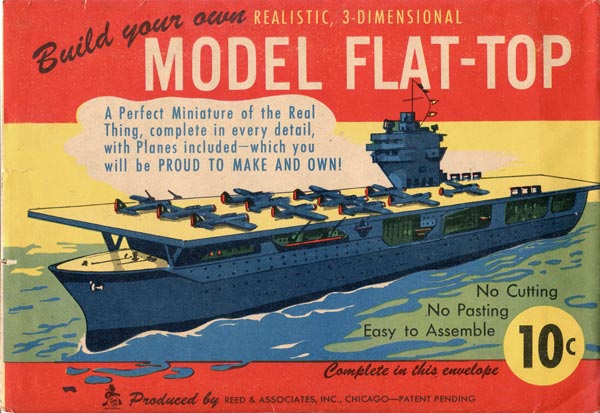

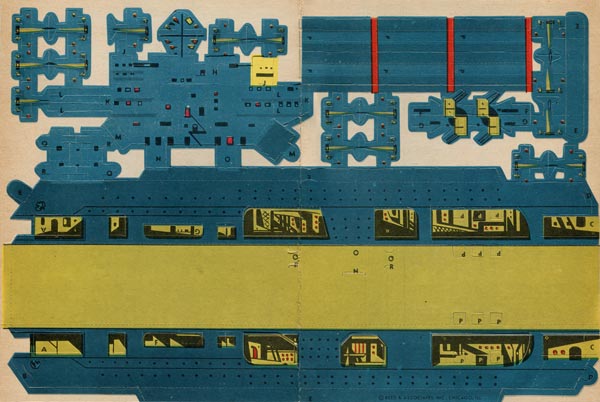

Judd Reed is likely the designer of two ship models that Reed & Associates produced in 1944 and 1945 also without a distribution partner. Both were 10¢ models printed on a single sheet of cardstock and packaged in an envelope similar to the earlier Hingee and Fawcett toys. Unlike Reed's fighter planes, the "Flat-Top" and "Battleship" are not replicas of any particular real-life ships. The two models are die-cut, but challenging to assemble. Indeed, one later employee of the company remembered that salesmen demonstrating the Battleship model were not able to build it themselves, and the toy was a flop.12

Build Your Own Realistic, 3-Dimensional Model Battleship, Reed & Associates, ca 1944-1945.

Build Your Own Realistic, 3-Dimensional Model Flat-Top, Reed & Associates, ca 1944-1945.

After the War

Though the war ended in 1945, some restrictions of metal used in manufacturing lasted until the early 1950s. Many toy companies were experimenting with a new production material: plastics. In 1946 Reed & Associates created a plastic novelty weatherhouse in the form of a miniature Catholic church, which was a great seller. The following year they invested thousands of dollars to produce a set of miniature plastic stained-glass windows which could be attached to Christmas tree lights. Unfortunately, due to manufacturing defects and poor timing, the product did not sell enough to recoup the company's investment and they lost thousands of dollars. Reed & Associates went bankrupt in January 1948.

Two weeks later, Marvin Glass restarted the company with new investors and new employees as Marvin Glass & Associates, a company which would become well-known in the following decades as a hit-making toy and game design company. Judd Reed and Eoina Nudelman stayed on employees of the new company. Both had a hand in the design of many plastic novelties for the company, and even some famous toys such as the board game Mousetrap. After the war, Nudelman did some side work as a childrens book illustrator for Whitehall Publishing, where he designed several toy cutouts similar to the "Funny Animals" toys, but the two artists did not return to paper model publishing together.

A German version of this article appears in the 2023 Zur Geschichte des Kartonmodellbaus journal published by the Arbeitskreis Geschichte des Kartonmodellbaus (AGK)

A complete list of published paper model work by Reed & Associates:

References

1 Eoina Nudelman passport application, February 1924. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

2 Bill Paxton: A World Without Reality: Inside Marvin Glass's Toy Vault, 2019.

3 Ibid.

4 Wallis Rigby: "Why Not Paper?" Playthings Magazine, February 1942. Reprinted in Charles M. Province: Wallis Rigby: Paper Model Monarch, CMP Publishing 2020.

5 Peter Wyden: "Troubled King of Toys," The Saturday Evening Post, Mar 5, 1960.

6 Andrew Clayman, "Electric Corp. of America, est. 1942", Made in Chicago Museum, Sep 29, 2018.

7 Emery Hutchison: "Toy is Fun, But its Birth is Painful," Chicago Daily News, Nov 9, 1944.

8 John Craig: "Stories of the Day," Chicago Daily News, Jun 6, 1943.

9 Joseph Starr v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Oct 13, 1954.

10 Emery Hutchison: "Toy is Fun, But its Birth is Painful," Chicago Daily News, Nov 9, 1944.

11 Peter Wyden: "Troubled King of Toys," The Saturday Evening Post, Mar 5, 1960.

12 Eddie Goldfarb quoted in A World Without Reality: Inside Marvin Glass's Toy Vault.