M. Buehler & Bro. Publishers

Maxmilian Buehler and his brother Emil grew up in the town of Bühl, near the Rhine River, in the modern state of Baden-Württemburg, Germany. Maxmilian was born in 1847 and Emil in 1852. Max immigrated to Philadelphia at age 19, married and started a family. In early 1872 he was able to bring his younger brother Emil to America as well. Soon thereafter, Max opened a stationery and book shop with his brother as partner in the Northern Liberties neighborhood in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia City Directory (1874)

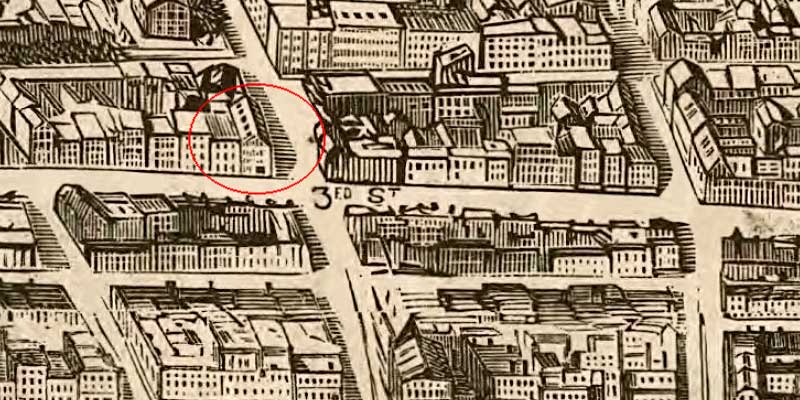

The shop and the brothers moved several times in the mid-1870s from locations on 3rd to 6th to 4th streets. From 1873 to 1876 the brothers lived at 546 N 3rd Street along with Max's wife Rosa, daughter Ida and infant son Eugene. Presumably the stationery shop was run out of a room on the ground floor at the front of the apartment, although in 1876 the city directory lists an additional store location at 615 N 2nd Street. The building at the southwest corner of 3rd & Green Streets is circled in this contemporary wood engraving map with north oriented to the right.

Southwest corner of 3rd & Green streets, detail of Bird's eye view of Philadelphia, Harper & Brothers (1872)

In America and Europe, colorful multi-plate lithograph prints were popular collectibles and wall decorations. The printmaking firm Currier & Ives declared in 1872: "our prints have become a staple article," and these cheaply-available artworks decorated many American middle-class homes. How popular such prints were to the customers in a lower-class neighborhood of the Northern Liberties is unclear, but the Buehler brothers shop was successful and remained in business for a number of years.

Passenger records show that Emil returned to Germany for a short visit in the fall of 1874, and Max in 1875. Most likely they visited family in Bühl, but perhaps these were business trips as well, to purchase prints which could be sold at the stationery shop. In addition to the genre prints popular in the U.S., a new kind of lithograph print was gaining popularity in France and Germany: colorful and complex paper cutout toy kits.

West of Bühl in the town of Épinal, France the first architectural paper model cutout designs were produced in 1862 by the Pellerin and Pinot & Sagaire publishers, which were popular enough that hundreds of other complex and varied paper model lithograph prints followed. In northern Germany, the firm Oehmigke & Riemschneider outside Berlin began publishing paper models in the late 1850s, and David M. Kanning in Hamburg released a series of architectural models starting in 1866.

Perhaps as teenagers in Germany Max and Emil had been lucky enough to acquire some of these newly-invented toys and enjoyed putting them together. Or they became familiar with them as grown-ups dealing with stationery and printed material for their shop.

Back in Philadelphia, the entire city was preparing to host the grand Centennial Exhibition in the summer of 1876. The festival commemorated 100 years since the Declaration of Independence was signed at the old Pennyslvania State House (now known as Independence Hall). After a site at Fairmount Park was chosen in 1870, engineer Herman J. Schwartzmann began planning the layout of the exhibition and its buildings. The grounds would feature five main exhibit halls as well as 200 smaller buildings. The Main Exhibition Building was the largest building in the world when it was completed. Exotic Horticultural Hall was styled after London's famous Crystal Palace, and Machinery Hall featured the massive Corliss Steam Engine which powered many of the machines at the exhibition.

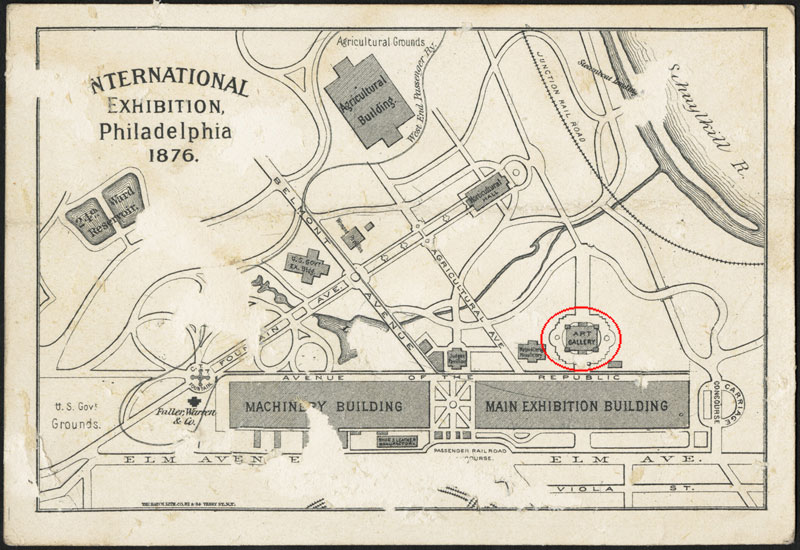

Memoral Hall Art Gallery highlighted on International Exhibition Philadelphia (1876) map from Wikipedia

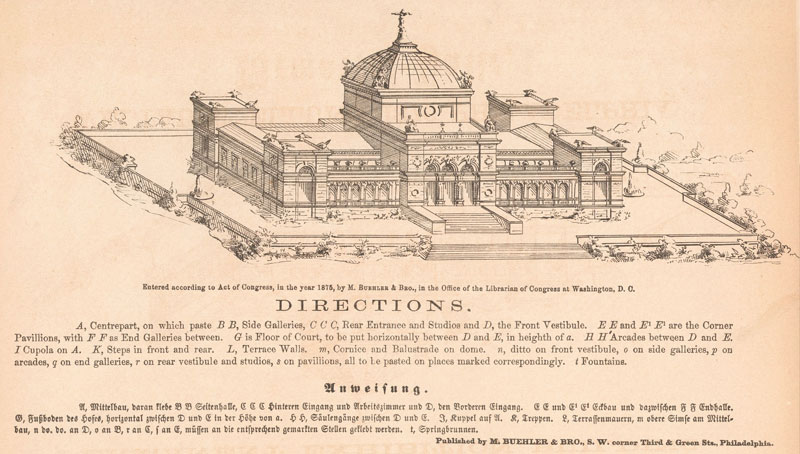

Despite these wonders, Max and Emil Buehler were more interested in the smaller Art Gallery building (also known as Memorial Hall), perhaps because they were dealers in fine prints and artwork themselves. The Beaux-Arts style building designed by Schwartzmann was built as a permanent structure to remain after the exhibition. It was the first purpose-built art museum in the U.S. and a model for later institutions such as the Art Institute of Chicago, Milwaukee Public Museum, Brooklyn Museum and many other neoclassical art museums. The building measured 365 feet by 210 feet, with a 150-foot high dome topped by a 23-foot statue of Columbia flanked by numerous other allegorical figures.

In 1875 Max and Emil copyrighted what is most likely the first commercial paper model in America, well before the building was completed in March 1876. They were prepared to sell the prints as souvenirs to visitors when the exhibition opened in May. Fortunately for modern-day modelers a copy of the kit survives in the collection of the Free Library of Philadelphia, which has posted complete scans online.

Completed model of Memorial Hall (1875)

The Memorial Hall model is very attractively printed in three colors on four sheets about 9" x 11" in size. There is no title on the first sheet of the set, as it was originally packaged in an envelope, which is not pictured in the scans. The kit is complex, with 74 pieces and 28 small figures to place around the finished building. The completed model is about 9 inches wide, which makes it roughly 1:485 scale in comparison to the actual building.

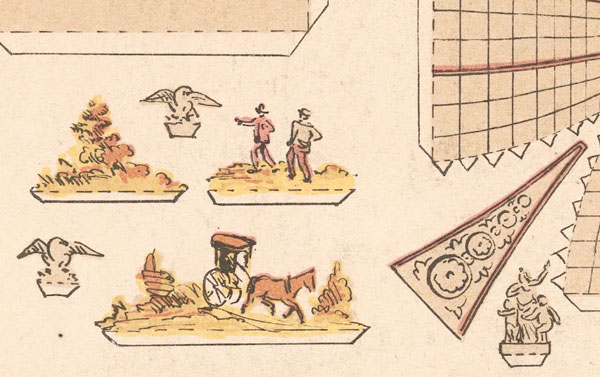

Detail of Plate 3 of Memorial Hall model (1875)

The small figures and ornaments are deftly illustrated in a loose and confident hand, which might indicate that a professional artist drew the illustrations, not Max or Emil Buehler. Did one of the brothers figure out the engineering of the model and then hand off the drawing to a commercial artist? Or were they simply publishers of a design made entirely by someone else? There is no credit listed for anyone else who might have contributed to the design of the model, so it is difficult to know.

The model uses many of the same conventions as contemporary French and German paper cutouts, such as dotted lines for folds, thick outlines and plenty of supplemental figures, but there are some significant differences. Most European models at this time were printed on single rather than multiple sheets, sometimes at large sizes, such as the Grandes Constructions series by Pellerin which measured approximately 15" x 18". Perhaps the smaller 9" x 11" sheets of the Memorial Hall model were designed to make an easier-to-carry souvenir for visitors spending a long day wandering the Centennial Exhibition.

Directions on Plate 1 of Memorial Hall model (1875)

Another interesting difference from earlier model designs is the inclusion of directions. It may seem surprising to modern modelers, but the European paper kits of this time period did not include instructions except for tiny thumbnail images of the finished model to give clues on how to put it together. The drawing of the completed model on the Buehlers' Memorial Hall kit is much larger and featured on the front cover rather than a footnote hidden in a corner. Below it are written instructions in English and German, as well as a handful of pieces for the model. If the designer had chosen, the entire kit might have been squeezed onto three pages rather than four, making it cheaper to print, but instead the illustration is given a prominent place to advertise how attractive the model might be when complete.

In the 1878 Philadelphia City Directory, the Buehler & Bro. partnership is listed as a frame shop rather than a stationery store. After 1880 the business is no longer listed, although both brothers continued working as framemakers, perhaps working for someone else. Max found a position with a frame shop downtown at 729 Market Street. Emil disappears from the historical record after 1886, and in 1893 Max left the city with his wife and three children for Indianapolis, where he found work as a travel agent and later returned to picture frame sales.

Max and Emil Buehler did not publish any other known model kits. Was the Memorial Hall model a successful seller? How many copies were originally printed? While complex paper kits flourished and evolved in France and Germany, the first paper model in America apparently did not lead to further designs. Artist Reginald Sperry produced two well-designed papercraft kits a few years later, but for decades afterwards, most paper models published in America were simple cutouts aimed at young children. Nearly 90 years later, Monte Models revived popular interest in complex paper models of American architecture.

Jack E. Boucher photo of Memorial Hall (1872) from Wikipedia

After the 1876 Centennial Exhibition closed, most of the buildings on the site were demolished or sold. The Main Exhibition Hall reopened as a musem but was not a success and the structure was torn down. The extravagant Horticultural Hall survived as a conservatory until the 1950s. Memorial Hall is the only major building remaining to the present day. The building became the home of the Philadelphia Museum of Art until it moved to its current location in 1928. After that, the building found use as park offices, a recreation center and a police station, but was falling into neglect by the early 2000s. From 2005 to 2008 it was restored as a new home for the Please Touch Museum. Interestingly, an original scale model of the Exhibition grounds was discovered during the building restoration. On display in the Please Touch Museum today, visitors can compare the tiny Memorial Hall in the official Centennial Exhibition model to the contemporary Buehler Brothers souvenir papercraft version.

Scale model of Memorial Hall at Please Touch Museum. Photo by Laura Blanchard (Flickr).

A list of known published paper model work by Max & Emil Buehler:

| 1875 | Souvenir model of Memorial Hall at the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition. In collection of Philadelphia Free Museum and Library of Congress |

References

Arkitektur aus Papier, Dieter Nievergelt, Musée historique de Lausanne, 2001