The Toll House Uprising

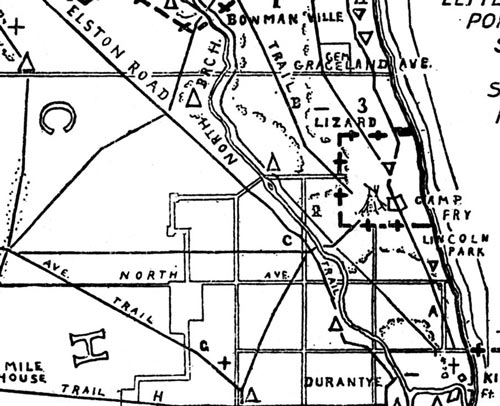

The long diagonal route of Milwaukee Avenue is a clue that this road existed before the right-angle grid of city streets was built around it. Centuries before Chicago existed, Native Americans walked paths across the prairie along the west side of the Chicago River toward villages and hunting camps in what is now Forest Glen. Later travellers on horseback and in wagons followed a loosely-defined track across the prairie, meandering around low-lying wet areas. This network of trails eventually was paved to become Elston Avenue. The history of Milwaukee Avenue is more recent.

Detail of Albert F. Scharf's 1900 map of Indian Trails and Villages of Chicago as they existed in 1804

After the Potawatomi were driven from Illinois by the Treaty of Chicago in 1833 after the end of the Black Hawk War, government surveyors began dividing the open prairie land into sections and parcels. New Yorker Martin Kimbell arrived in 1836 and settled on 160 acres southwest of what is now Diversey and Kimball.

Kimbell and later settlers harvested hay or plowed the prairie to plant crops. The market for their produce was Chicago, but the journey across the prairie could be difficult due to mud or dust, or impassable in springtime. For farmers living farther from the city, the trip might take several days even in good weather.

In 1849 the state granted a 99-year charter to the Northwestern Plank Road, the first of several long-distance toll roads connecting outlying towns to Chicago on compass points. The new road cut diagonally eighteen miles across open land from the Des Plaines River near Wheeling to the west side of downtown, not far from Haymarket Square on Randolph Street where farmers sold their produce. At the western end the road divided into several smaller branches.

Martin Kimbell was hired as superintendent to build the section of roadway through Logan Square and maintain it. Workers levelled a 16-foot wide roadbed and dug ditches alongside for drainage. In low-lying areas they placed thick planks sideways across stringers laid on the ground to raise the roadbed above the mud. There are several colorful legends telling how tavern owners along the way persuaded the surveyors to steer the road toward their establishments, but the finished route is a straight line with only one bend near Irving Park Rd.

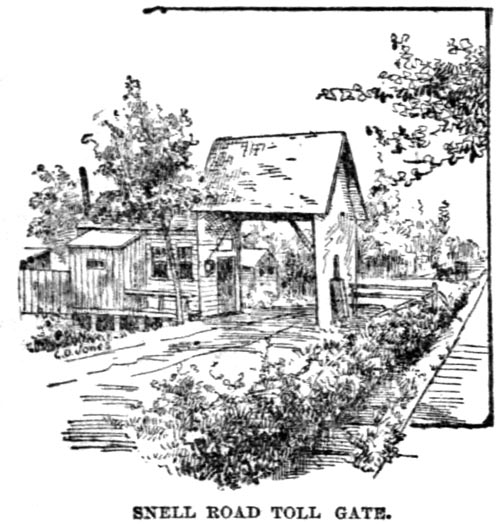

West of the Chicago city limits at Western Ave, the Plank Road was a toll road. The frame toll house which stood there was moved at some time in the 1870s to the northeast corner of Fullerton Ave (about in front of the modern 7-11). Seven other toll houses were located every few miles at Belmont, Jefferson Park, and farther down the road. The toll-keeper lived in the six room house and was on duty 24 hours a day to collect fares from travellers. A carriage drawn by four horses paid 4¢ per mile, a wagon drawn by one horse was 2¢ per mile, a horse and rider owed 1¢, and smaller amounts were due per sheep, hog or goat driven along the road.

1889 Tribune illustration of one of the toll gates (not at Fullerton)

The toll house stood partway across the roadway, and at night a pole was lowered and padlocked to block passage. Anyone travelling at night would have to wake the toll-keeper and wait for him to unlock the gate. Signs warned travellers that sneaking around the gate would cost them a $25 fine. At times the toll-keeper chased down cheaters and even threatened to beat those who did not pay their fare.

After almost two decades of use, the road was in need of repair. Jefferson Park real estate investor Amos Snell purchased the charter for the Northwestern Plank Road in 1870 and agreed to finance repairs. Snell added gravel over the planks in the wet areas and dredged the ditches.

William Ringler

William Ringler worked for Snell as toll-keeper at Fullerton for fourteen years in the 1870s and 1880s. He later recalled with pride how he had managed to collect $790 on one busy Sunday from travellers headed to picnic grounds outside the city. The average take per day was usually $300 to $500. Ringler made a point to collect exact fares from wealthy carriages and farmers wagons alike. Even firemen and police officers had to stop and pay to pass.

Within a few years the roadway was in rough shape again. Local residents as early as 1878 complained to the county board that the road was a nuisance and that the tolls collected were obviously not used for keeping it in good condition. By 1889 a Daily News reporter described the conditions of travel on a winter day:

From Armitage avenue to Fullerton avenue, the most frequently traveled part of the road, is a dreary waste of mud, averaging three or four inches in depth. It isn't that clean, bearable sort of mud found on country roads, which is just the natural result of rain on the soil. But it is a cold, clammy, clinging kind of mud, the mixture of a thousand ingredients. It is just as if all the ugly things said about the Snell road by those who have to travel on it, and all the things they have thought and haven't said, and all the unconscionable impositions of which the management have been accused, and all the hard, unkindly feelings ever indulged in by the owners of the road or the patrons were real material entities and had been mixed up and reduced to a paste and spread on the road... The mud is of a smooth unctuous character, of the consistency of soft mortar... It is just of that quality that makes it spatter readily. A horse or vehicle passing through it soon becomes thoroughly plastered with it.

Meanwhile Amos Snell amassed a fortune of a million dollars and become one of the wealthiest citizens in Chicago. He built a mansion on Washington Boulevard near fashionable Union Park. In 1881 he sold the western branches of the toll road to the county, but kept the three most lucrative toll booths at Fullerton, Belmont and Jefferson Park.

The city was growing around the toll road as the truck farms were subdivided and filled with cottages and two-flats. Lyndale and Belden streets just off Milwaukee were subdivided by developers John Johnston Jr. and Edwin Hinsdale in 1881-1883. The toll road in the midst of city streets became a hindrance to travel and a nuisance to local residents who lived next to it.

The new streets provided ways for scofflaws to detour around the toll gate. A news article from 1886 mentions farmers using Belden as a side street to avoid the toll gate at Fullerton, though it is more likely they went down Medill, since what is now Sacramento Ave did not then connect to Belden. Snell made plans to build another toll gate at California to capture the detourers, and stockpiled supplies for its construction. Emanuel Buresh and John O'Fenloch, who both lived at California and Milwaukee next to where the new gate would be built, sued to stop its construction, arguing that it would obstruct access to their property unjustly. While the lawsuit was in court, local residents from Belden and perhaps Lyndale Street stole the long pole that Snell intended to use for the gate and chopped it up for firewood.

In February 1887, voters in Section 36, which encompassed land south of Fullerton and east of Kedzie, voted to join the city. The stretch of Milwaukee south of Fullerton was now within city limits, though Snell's charter only allowed collecting tolls outside the city. In June 1889 the rest of Jefferson Park township was annexed to the city.

After Amos Snell was murdered in his home in February 1888, his heirs continued collecting tolls, arguing that Snell's charter was part of their inheritance. The Chicago city council resolved that the toll houses were illegal and should be dismantled within five days, but political efforts to remove the tolls got bogged down in the courtroom and the toll-keepers kept collecting tolls.

Local residents grew tired of waiting for a legal judgement. Rumors spread that someone should burn the hated toll houses down. Later, saloonkeeper Joseph Kandlik claimed the plot was hatched at his barroom at the southeast corner of California and Milwaukee.

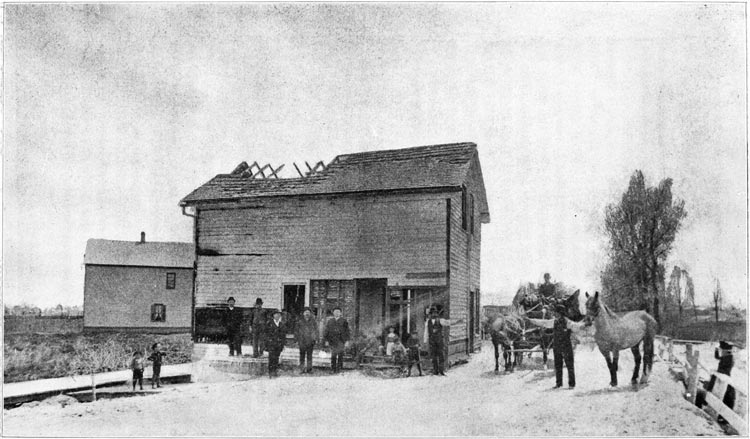

William Landshaft's photograph of the Fullerton toll house on May 3, 1890, reproduced in Alfred Bull's 1911 The Township of Jefferson Ill.

On Wednesday night, May 1, 1890, a posse of forty to fifty men in wagons drove up to the Fullerton toll gate and confronted toll keeper Ed Smith, telling him to pack his bags and get out. They smashed the small gate house and gate pole and pushed the wreckage into the ditch, then rode on to the Belmont toll gate and did the same.

That Friday around midnight an even bigger crowd of as many as 200 marched on the toll house, shouting "Smash them down!" Ed Smith and his wife ran to alert the fire department. The crowd first placed many of the Smith family's belongings out on the curb and then set fire to the toll house. As the flames grew, the people ran excitedly around the bonfire. Police and fire crews soon arrived, doused the flames and arrested six men for arson.

While some modern-day retellings blame frustrated farmers for burning the toll booth, it was more likely neighbors living on the new streets around Milwaukee who were fed up with the toll road obstruction. How many long-ago Lyndale neighbors were in the mob that night?

The following morning, William Landshaft, a house painter and amateur photographer then living at 2903 W. Belden, set up his bulky tripod in the street and captured an image of the burned toll house. Several men and boys stand on a platform in front of the house, and a man holding a horse signals to another. The embers from the fire must have cooled, as it appears a woman or girl is sitting inside a damaged doorway of the house.

To the left is a glimpse of still-remaining prairie, several feet below the level of the road. On the right, a curb of Fullerton can be seen, which ran behind the toll house. Beyond the curb is another patch of prairie and in the distance a few of the new houses along Belden Ave.

Two weeks after the burning of the toll house, the Illinois Supreme Court decided: Snell's toll road charter could not be inherited and all of the toll booths must go. Milwaukee Avenue would become a regular city street and in time it would be lined with houses and businesses covering over the prairie.

In the early 1900s, former toll keeper William Ringler ran a saloon at 2900 W. Fullerton, the building seen behind the toll house. No doubt the story of the uprising was told and retold there until it became a bit of a legend. Perhaps it was also told a few blocks away, where Charlie Kandlik eventually inherited his father's saloon at California and Milwaukee.

72-year-old Kandlik retold the tale in all its detail to a skeptical Tribune reporter in 1955. In his version he knew all the leaders of the plot personally. He saw them all dancing around the fire in Indian headdresses like a latter-day Boston Tea Party. And in the famous photo from the next morning, that was him right there on the left.

The colorful legend has captivated many over the years. In 1928 and 1939 neighborhood festivals in Jefferson Park staged a pageant reenactment of the legendary incident that allowed free travel for all on Milwaukee Avenue.