The Mayor's Friend

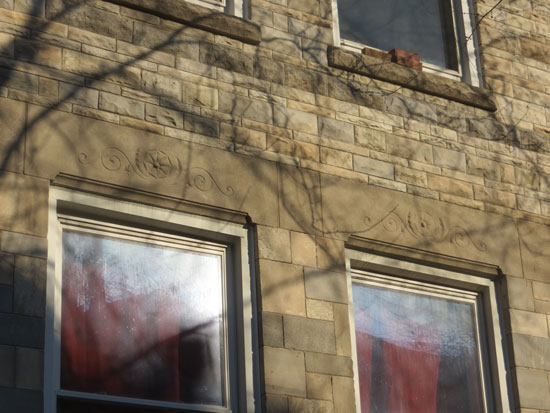

The house at 2834 W. Lyndale looks at first glance like a typical Logan Square greystone. The façade, however, lacks the sculptural depth and unified ornament of that style. The building is more similar to a flat-fronted Victorian rowhouse with an oversized cornice. Closer inspection reveals that the front wall is made of different types of stone on each story, as if it were put up in stages.

Close-up of the variety of stonework on the façade of 2834 W. Lyndale

The house at 2834 was built in the early 1880s, a decade before the heyday of Chicago greystones from the mid-1890s to 1910. Pasquale Mesce purchased an empty lot here from developer John Johnston Jr. in January 1882 for $275. Mesce was born in Tuscany in 1845 but grew up in Naples where he learned the trade of stone cutter. He left his wife Isabella and four children to come to America in 1874. In Chicago he found work on the many buildings going up in the years after great fire. By 1880 Mesce had saved enough to bring over his wife and children. The family would go on to have seven more kids, so Pasquale built this tall three-flat to house them.

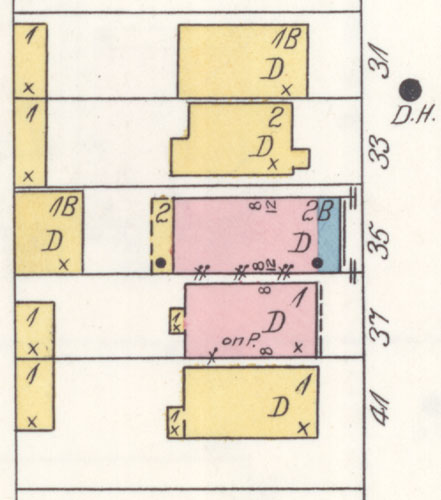

The colors and symbols on the map below describe the construction of the Mesce house at 2834 (#35) with its foot-thick brick foundation, basement, flat gravel roof, stone façade and tin cornice. There was an extra apartment in the frame coach house in back. The Petosa house next door at 2836 (#37) had 8-inch brick walls, a wooden cornice and shingle roof. These two were the only masonry buildings on a street of wooden houses.

Detail of 1896 Sanborn Insurance Map. Source: Library of Congress

The Chicago History Museum collection includes an absorbing, rambling memoir written by Pasquale's grandson William Mesce Peck, who remembers his grandfather Mesce fondly. He asserts that Pasquale never had a cavity, despite never brushing his teeth. He owed his good health to a diet of cheese and fruit at every meal. Peck's memoir is based on family memories and contains a large number of factual inconsistencies, but it provides a vivid portrait of his family in early Logan Square.

Peck writes that his grandfather had worked as a stone mason on several post offices on the Northwest side. He was especially proud of the "Pony Express" cartouches he carved with the logo of the postal service over the door.

Stone "Pony Express" medallion possibly carved by Pasquale Mesce, above the door on the former post office at 1402 N. Western.

Mesce went into business for himself and opened a stone yard at the corner of Rockwell and Milwaukee. When young William Peck grew up, neighbors often pointed out which greystones around Logan Square his grandfather had carved ornamentation for or helped build.

Peck's grandmother Isabella was born in Naples in 1849. Like her neighbor Maria Gaetana Petosa, she must have had a busy life taking care of her many children. Peck writes that she was pregnant nineteen times, though the records list only ten children who grew up in the house on Lyndale.

Vito, or William as he was known in America, was the oldest child. He worked as a stonecutter, most likely for his father's business, and played semi-pro baseball in his spare time. He was a 31-year-old bachelor living with his parents at 2834 in 1902. In August of that year William went to a family party at a picnic grove in rural Niles Center. Some men at a nearby table argued and a fight broke out. William intervened to assist an older gentleman and someone with a knife stabbed him in the side. His family put him in a wagon and raced for miles to the nearest hospital, but tragically he did not survive the journey.

Over the years the older children married and the large family grew larger. Some siblings moved into the coach house behind the building or rented an apartment at 2832 next door. Daughter Mary married Michael Boskelly in 1905 and bought the house at 2922 W. Lyndale where they raised their family. Son James married Lulu Goodman in 1906 and the couple rented an apartment at 2826. Lulu's half-brother Adolph Beckman later bought the house at 2869 W. Lyndale. Pasquale and Isabella moved to a new house at 2423 N California Ave in the mid 1910s, though they kept the old house at 2834 as a rental property.

Most of the sons in the Mesce family got their start as stone cutters in the family business. After about 1908, Pasquale Mesce sold the stone yard location on Milwaukee to his son-in-law Orlando Pecchia who built a wagon factory there. The Mesce stone yard moved to a larger property at 1659 N. Western Ave.

Frank and his brother Tony Mesce started their own construction business in 1910, but Frank soon found more lucrative work as a building appraiser. He became close friends with neighbor Magne Michaelson and eventually rented a room with the Michaelson family at 3004 Palmer Square.

1925 Chicago Tribune portrait

Magne Alfred Michaelson was a public school teacher who was then just getting his start in politics. He was elected alderman of the 33rd Ward on the Republican ticket in the spring of 1914. When William Hale Thompson won the mayoral race the following year, the Republicans took the reins of the city and control of its budget.

Thompson earned the nickname "Big Bill the Builder" for ambitious infrastructure projects. Thompson built many of the projects proposed in Daniel Burnham's 1909 Plan of Chicago, such as the Michigan Avenue Bridge, which drew downtown development north of the river. Frank Mesce was hired as an appraisal expert to assess the value of property to be compensated when the city widened the former Pine Street to become Michigan Avenue north of the river. William Peck credits his uncle as the thoughtful planner who saved the Water Tower by routing Michigan Avenue around it, though its unclear how true this family story might be.

Frank Mesce became fast friends with Mayor Thompson. He joined the mayor on a post-election victory tour out west, and a newspaper photo from that time shows him wearing a 10-gallon Stetson, Big Bill's trademark, with the rest of the mayor's crew. Nephew William remembered him as a man of elegant taste in suits, cars and women. He was an extrovert who drew attention. Soon Frank's brother-in-law Mike Boskelly was working as Thompson's driver, and his little sister Pearl got a job as a secretary at city hall.

1915 tour stop in Minneapolis: Senator "Big Ed" Smith, Minneapolis Mayor Wallace Nye, "Big Bill" Thompson, Guy Howard, and Thompson's friends Dempsie, Rhome, Pettitt & Frank Mesce

When the city made plans to widen Western, Ashland and Ogden avenues in 1919, Frank Mesce and business partner Austin J. Lynch signed a contract with the city to receive a commission of 2% of the value of the buildings assessed. With so many buildings impacted along the widened streets, the appraisers raked in over $40,000 in fees each year of the project, more than double the mayor's salary. The Chicago Tribune, no friend of Mayor Thompson's administration, brought a $2.9 million lawsuit against Mesce, Lynch, Thompson and two other city employees claiming that the consultants overvalued the properties in order to collect exorbitant fees from city coffers.

By this time, Frank Mesce's friend M.A. Michaelson had been elected to the U.S. Congress. Michaelson sent a letter to President Warren G. Harding asking for "a square deal" in the matter, and the president returned the favor by sending a word of support through his cabinet to the Chicago district attorney and local IRS collector. The lawsuit dragged on for eight years. Though the Tribune eventually won, the Illinois Supreme Court later overturned the verdict and exonerated the appraisers and the mayor of any wrong-doing. A separate lawsuit filed by Mesce to recover unpaid fees took fourteen years and was finally rejected by the Illinois Appellate Court.

After all that drama, Frank Mesce moved back in to the family house at 2834 where he lived with his sister Catherine and her husband Frank Johnstone until his death in 1949. The house remained owned by the family until 1978.