Alone in the Gift Shop

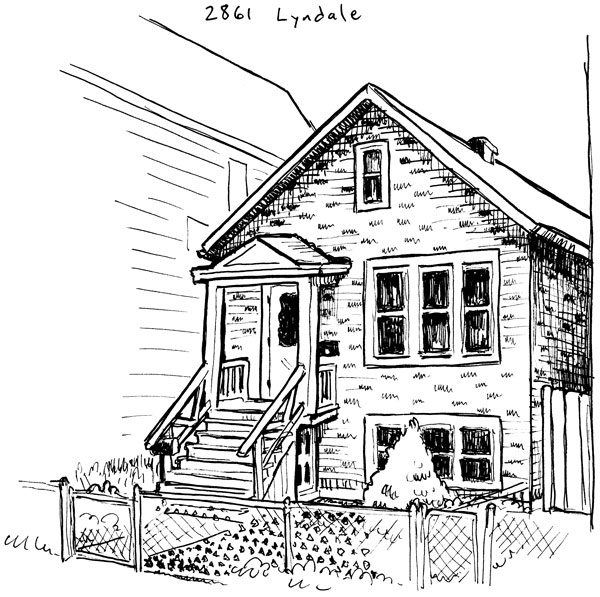

Nels & Marianne Anderson purchased the house at 2861 W. Lyndale in March 1909. Nels had three children by his first wife Bessie, who passed away shortly after young Nels Jr. was born. Less than a year later he married Marianne and had two more children before moving to Lyndale St. When the family moved in to the house, 10-year-old Ellen was the oldest, and baby Ruth was born about a year later. Nels worked as a machinist at the International Harvester Tractor Works to provide for his large family in their little house.

Marianne passed away in 1920 at age 44. The other children moved out of the house without leaving much of a paper trail for writers to follow, while Ellen stayed living with her father. She found work as a telephone operator in an office.

In November 1932 she may have seen a large ad in the Tribune with an eye-catching headline:

For a fee, the Central Rental Service would provide advice, market research and references to help young entrepreneurs get started. One of the available locations listed in the ad was not too far away, an 18- x 35-foot storefront space in the Congress Theater building at 2125 N. Rockwell.

Undaunted by the chauvinistic tone of the ad, perhaps Ellen had her own dreams of freedom from the doldrums of office work. In 1933 she opened the Milshire Gift Shop:

Sponsor ad in St. Sylvester Church Golden Jubilee program, November 1934. Courtesy of Logan Square Preservation.

The Congress Theater was built by the Lubliner & Trinz movie chain in 1926. A grand Beaux Arts palace with seating for 2,900 moviegoers, the building also contained 56 apartments and 17 street level retail spaces. Though Ellen's store was around the corner from the theater entrance, there would have been thousands of possible customers coming and going before and after the matinee and evening shows. Even in the midst of the Great Depression, movie tickets and greeting cards were cheap and affordable diversions.

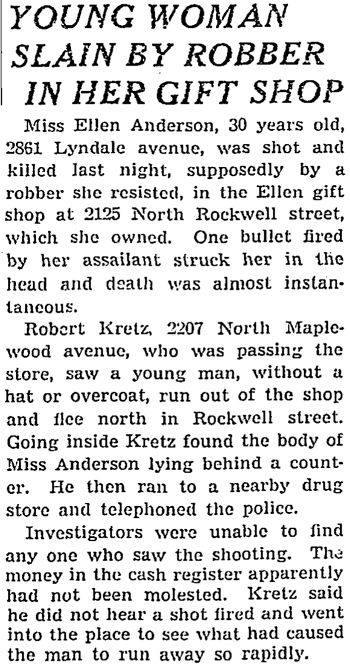

On Saturday evening, October 19, 1935, Ellen was in the gift shop alone when a young man entered, as described in the Chicago Tribune the next day:

Neighbors assisted police in searching for the perpetrator, but with only a vague description to go on they made little progress. Detectives discovered that $15 had been taken from a hiding place in the back of the gift shop in the robbery, but no other clues or arrests were reported.

Several months later, Chicago was captivated by the mysterious disappearance of prominent pediatrician Silber C. Peacock. The doctor had received a late-night house call to see a sick child but never returned. A few days later his badly-beaten body was discovered in the back of his Cadillac on an undeveloped North Side street near the city limits.

Detectives searched the doctor's files for a motive for the murder, and the tabloids entertained sensational scenarios of adultery, vengeful enemies, drug deals and back-door abortions, but none of the theories explained why he had been so brutally killed.*

In March 1936 police arrested four teenagers. The boys confessed to a string of muggings of doctors lured to dark gangways and alleys by similar fake phone calls. They had been drinking in a Division St. poolhall that night and picked Peacock's name at random from a phone book. He was killed simply because he resisted and angered them. The youths confessed to several other murders which had apparently started as robberies, including the murders of Peter Payer, a 65-year-old tailor who was working alone in a basement shop at 1934 N. Hoyne, and Ellen Anderson.

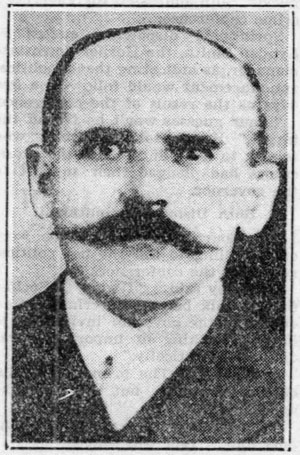

Peter Payer 1870 - 1935

The Peacock murder trial was covered extensively, but there is no mention of whether the murders of Payer and Anderson were ever fully investigated or prosecuted. During the trial, the four teenagers complained that they had been beaten by police into confessing. A reporter noted an obvious contradiction in their stories when one teen described in detail how he had participated in Anderson's murder, which happened at a time when he was in prison for a previous robbery.

Despite these inconsistencies, jurors found all four guilty and three received 199 years in prison. The purported gunman of the group, Emil Reck, appealed, and in 1961 his case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled 7-to-2 that his confession had been forcibly and illegally obtained. His sentence was dismissed and he was freed at age 44 after the state attorney declined a retrial.

*LeRoy McHugh's splendid noir-ish tale of the Peacock investigation is reprinted in the 1952 anthology This Is Chicago