|

The Shanghai Urban Planning Exhibition Center opened in 2000 as a museum showcasing the city's history and plans for its future development, the first of many similar urban planning exhibits in Beijing, Chongqing, and other growing cities in China. The large museum is located in an architecturally dramatic building on People's Square near other major municipal institutions such as the Shanghai Museum and Shanghai Grand Theater.

In the lobby of the museum, the visitor first encounters an abstracted gold pile of Shanghai's iconic landmark architecture nested in a flying saucer. This confection, titled "Morning in Shanghai", emblemizes the intent of the museum. Like a gilded Buddha in quiet repose on a lotus blossom, the idealized city rises from a bed of greenery but leaps skyward in dynamic movement and form. Though the buildings of Shanghai's tumultuous past form the base of the sculpture, the shiny skyscrapers above point the way ahead beginning a new day of prosperity.

Shanghai's most visible reminder of its past is The Bund's row of banks and foreign trading houses of the former International Settlement on the banks of the Huangpu River. Here, a monochromatic model shows the historic art deco skyscrapers of one of the world's most famous skylines. On the walls behind the model are displays describing improvement projects to the seawall and riverwalk along the Bund.

Opposite the Bund model is a smaller scale model which duplicates the Bund in less detail but also includes the Pudong across the river, a densely packed area of skyscrapers and high rises developed in the last 20 years. On the left is the Oriental Pearl Tower and on the right the stair step trio of supertall buildings: Jin Mao Tower, World Financial Center, and Shanghai Tower. Sadly the white plastic model was covered by a dark layer of grit and dust that is all too common in urban China, perhaps a bit of added realism to the otherwise glamorous idealized miniature city.

The second floor of the museum features a small history museum about the city with photos and newsreel films. Another gallery displays a half-dozen miniatures of historic landmarks in Shanghai, with lots of information about how the government is working to preserve some of the city's old architecture, despite rapid development. Here, a diorama shows a project to restore (or gentrify) a block of shikumen apartments, a unique housing style developed in Shanghai in the 1860s combining elements of Western and Chinese architecture. Shikumen means "stone warehouse gate" which describes the stone walls that enclose a small garden in front of the townhouses, with a heavy door leading to each individual apartment. In the rear of the building, a narrow longtang alley can be entered by an arched gateway. A majority of Shanghai's population once lived an estimated nine thousand shikumen houses in the city, but since the 1990s many thousands of these houses have been demolished to build denser high-rise buildings.

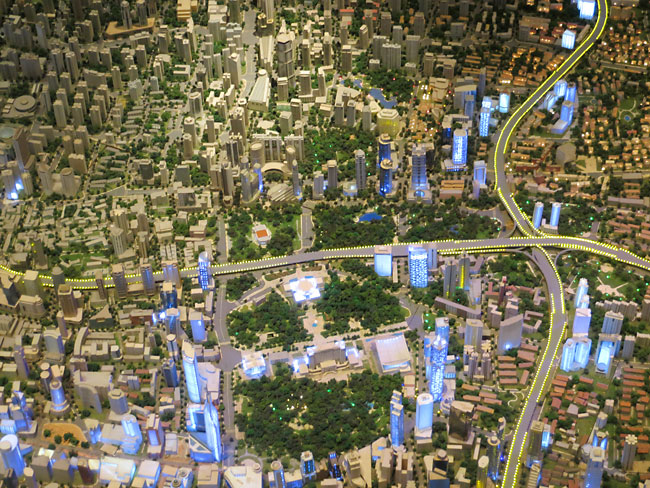

Leaving Shanghai's past behind, the visitor ascends to the third floor of the museum to see the main attraction: the huge 1:500 scale city model of future Shanghai. The model represents not the city of the present, but the master plan of Shanghai as it will look in 2020. The model encompasses the central part of Shanghai within the Inner Ring Road, an area about 9 miles by 5 miles. (The full city of Shanghai is about 58 miles by 55 miles, with three more expressway rings beyond the Inner Ring Road.) Four pillars interrupt the model at about 4 scale miles apart. The total size of the model is about 5200 square feet or 480 square meters.

A big green space near the center of the model is People's Square, and there is the tiny Urban Planning Exhibition Hall on the left side of the park (with a square awning). In colonial times the oval-shaped park was the site of a horse racing track and the center of the International Settlement elite social life. After the war and revolution the land was confiscated from its wealthy foreigner club members and given to the people as a public open space. In the 1990s the Shanghai municipal government built itself a new home at the center of the park and began siting other institutional buildings within the park, such as the Grand Theater to its right and the Shanghai Museum beyond the municipal building in the photo above.

The sinuous network of elevated highways across the city is emphasized in the model by strings of yellow LEDs. Some of the newer skyscrapers and notable buildings have blue or white LEDs inside to light up tiny plastic windows.

Every 10-15 minutes the overhead lights on the model dim and the buildings light up within, making a fairy tale of colored lights. Its unclear whether the lighted buildings represent new developments, or projected developments, or simply larger structures.

While the model is rich in detail of tiny trees, roadways and houses, its clear that not everything is 100% accurate in matching reality of the real places. Comparing this photo to a satellite view, we can see that the housing developments to the left of the park are similar to the real places, but not exactly correct in layout. As Shih-yao Lai notes from interviews with the builders of the model, in a number of places the model makers "improved" on reality by replacing blocks with the projected buildings that would possibly be built there, not just the future buildings that were not completed yet when the model was completed. In certain places the spacing between skyscrapers was exaggerated so that each would stand out a bit from its neighbors, though its not clear whether the spacing of streets around the skyscrapers was increased as well.

Though I am not familiar with much of Shanghai, I had just spent the morning walking around the blocks near Tomorrow Square, the pointed skyscraper above. The hostel where I stayed is on a small street behind the skyscraper, although in the model it has been replaced by a cluster of high-rise apartments. Perhaps the city planners intend to replace the low buildings around the hostel? In any case, the houses around here are in real life built right up to the street, or surrounded by high walls, not by the open grass lawns the model might lead you to believe. A tiny alleyway just to the left of the cluster of high-rises is ignored completely.

Another location on the model I had just explored in real life: the ancient Yuyuan Garden which was started in 1577 and is a famous and treasured site in Shanghai's Old City. The Mid-Lake Pavilion Tea House is visible at the center with its "Nine-Turn" zigzag bridge. The garden includes the lake and the area to the north (to the right in photo). The real garden is a 5-acre oasis, densely laid out with meandering pathways and little bridges over ponds and streams leading to teahouses, rockeries and decorative halls, all enclosed by undulating walls topped with dragon heads. Sadly the model does not capture any of those details of this picturesque local landmark. There are no tiny paths or ponds, and without the high wall along the street there is little of the mystery of this dense garden hidden in the city. The little street along the east side of the garden (below the lake in the photo) is in reality a narrow lane enclosed by high walls, not a suburban street lined with arbitrary trees, and the block of housing opposite the garden is crowded with houses and tiny courtyards branching off other narrow alleyways.

Despite the inaccuracies in the details of the model, at a distance its very impressive. Here is the famous Nanjing Road shopping street, leading from the corner of People's Square at the top and emerging on the Bund next to the Cathay Hotel on the bottom of the photo.

In the lobby of the museum behind the "Morning in Shanghai" sculpture there is a bas relief titled "Relocation of Millions of Citizens". The monument is meant to commemorate the cooperation of millions of residents who have agreed to allow the government to demolish their old houses and move into newly built housing. The construction of the Pudong area alone required the relocation of 300,000 citizens, and throughout the city over a million people were relocated. The scale of growth and development in Shanghai is only matched by the scale of demolition and forced relocation that preceded it. Whether the relocated citizens moved happily to their new houses or not, they did not have much of a choice in China's autocratic political system. The bigger picture of Shanghai's glorious growth into a world-class global power is more important than the small details of individuals and the small hesitations of nostalgia over old houses. In this way the Shanghai Planning Model is functions in a similar way to the Panorama of New York model when it was first commissioned by Robert Moses to showcase his massive redevelopment and freeway-building projects. The model was of interest to tourists at the 1964 World's Fair, but of perhaps more importance to residents who perhaps had never imagined themselves part of something larger than their individual street or neighborhood. The viewer can see the whole picture of the city and understand that these big projects are more important than the individual houses or people that might be affected to make room for new growth.

Looking down from the balcony, the twinkling lights and cute miniature plastic towers of the model are seductive, and the excitement of living in a world-class globalized city is thrilling. Who wouldn't be dazzled by this view and want to be part of making it come true? In the old "Iron Rice Bowl" communism of 30 years ago, citizens performed their obligations to the government and were taken care of in return as a Confucian bond. For citizens who might then have felt more connection to their own families and next-door neighbors or work-unit comrades and bosses, perhaps the Shanghai Planning Model represents a leap over these myopic relations to a larger relationship with the city of Shanghai itself. Will the citizen feel more empowered by this view, perhaps to push back against future demolitions and forced relocations of residents? Or will the view only inspire the individualistic dreams of modern Chinese capitalism, to capture a window office in one of the new skyscrapers with a view much like this?

Starting from the bottom floors of the museum showcasing the history of Shanghai, to the middle floors showing its projected future, the visitor climbs to the top floor cafe with a dramatic view over People's Square to the present reality of the city skyline, hazy air and all. Further reading about Shanghai's urban development: A History of Future Cities by Daniel Brook, W.W. Norton (2013) Visit other mini cities around the world |